The whiz of cars on Kennedy Rd. cuts through the sound of crickets singing and wind rustling through soy fields at Empringham Farms.

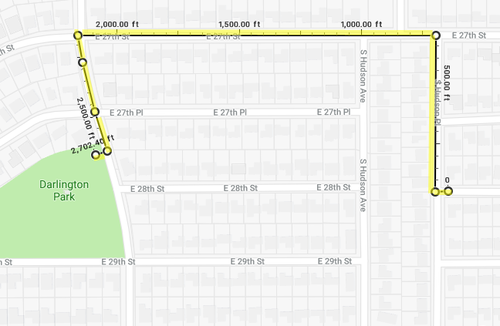

The busy north-south corridor can be “dangerous” for farmers moving equipment between fields, said Kim Empringham, who farms 800 acres with her husband.

They’re based on 10 acres in Stouffville, but they farm cash crops — corn, wheat, and soy — in fields from Markham to Newmarket. It can take an hour by tractor to travel between them.

Some of their equipment is so wide, it crosses the yellow centre line on narrow commuter roads that weren’t built for farmers.

At times, they have to stop what they’re doing and wait for rush hour to end, because “it’s just not safe,” she said.

It’s a familiar challenge for farmers in the GTA, but things could change: Ontario is developing an agricultural system in the Greater Golden Horseshoe to enhance the area’s agri-food industry. The sector contributed $37.5 billion to Ontario’s GDP in 2016.

The agricultural system will protect a continuous base of prime farmlands from development, support the services and communities critical to the farm and food industry and ensure farmers’ needs are considered in future infrastructure planning.

“It’s about making sure that the sector, as a whole, can survive,” said Empringham, who also serves as the secretary-treasurer for the York Region Federation of Agriculture.

For Janet Horner, the executive director of the Golden Horseshoe Food and Farming Alliance, a simple rhetorical question almost says it all: “Don’t you want to eat?”

“Protecting our land, so we are able to be somewhat self-sufficient and food secure is important. If we could eat houses, that’s fine, but we can’t,” she said.

Protecting those prime lands for food productions becomes even more important as the population of the Greater Toronto Area is expected to grow by 42 per cent by 2041 and productive farmland is under threat from urban sprawl.

Most of Canada’s prime agricultural lands have already been lost, said Keith Currie, the president of the Ontario Federation of Agriculture.

Just look out from the top of the CN Tower. “It’s all the best farmland that’s been developed. Essentially it’s entombed forever under asphalt and cement,” he said.

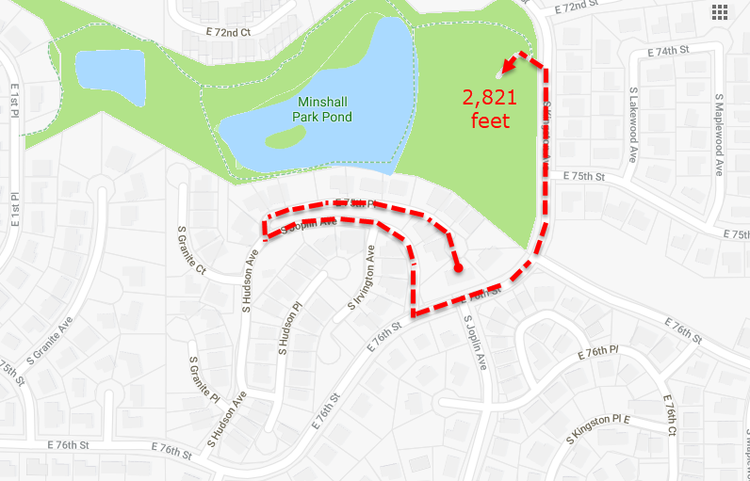

While some agricultural lands are protected under current policies, even the Greenbelt Plan, which protected some farmland, including most of the land Empringham farms, left prime agricultural lands outside its bounds.

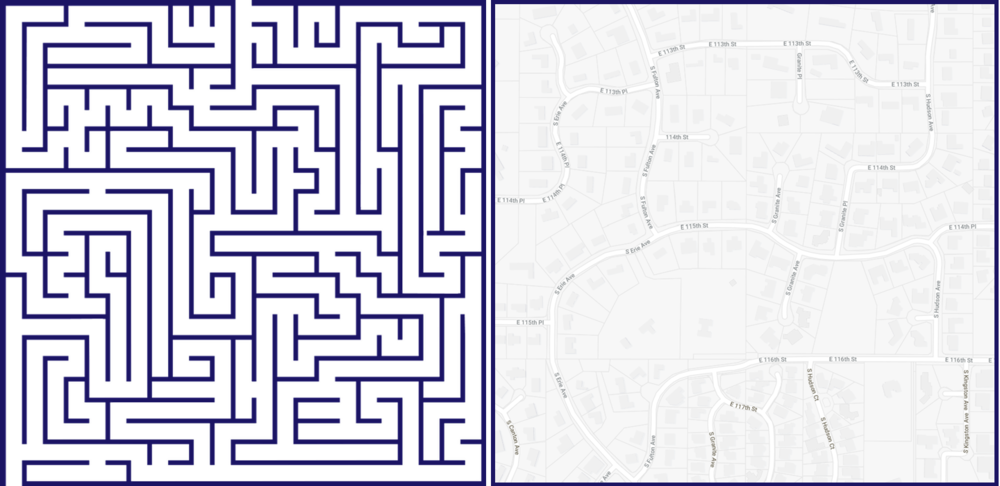

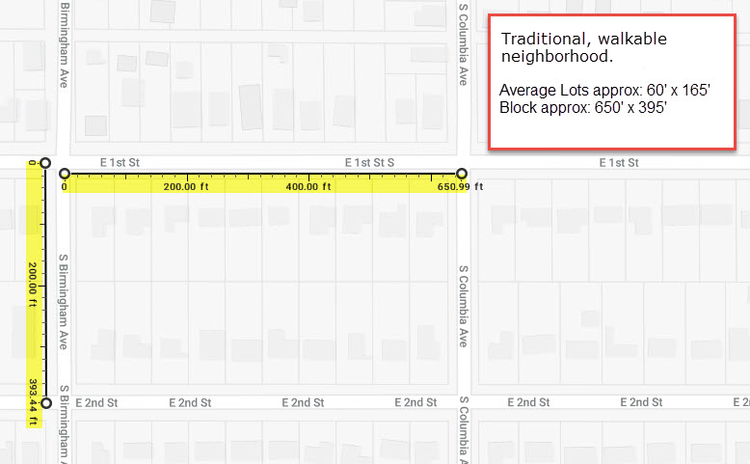

The urban development spreading outward from Toronto’s core has left farmland fragmented, at its worst creating farm islands in a suburban sea.

“When you’re surrounded by subdivisions, you can’t farm,” Empringham said.

The further your farm is from the other services and businesses that support you, the less competitive you are, she explained.

An agricultural system that ensures protection for a continuous tract of farmland creates an incentive for other agri-food businesses — vets, mills, equipment sellers and others — to expand or move into dense agricultural areas, boosting the economic outlook for farms.

For farmers, protected land can also give them confidence to plan long-term, without fear they’ll be squeezed out by development.

“We know we can stay here, so we can make improvements to the buildings, to the infrastructure that we’ve got here on our home base,” Empringham said.

Even if they sell, they know they’ll be selling to farmers, making investments in the farm worthwhile.

That’s not something she sees happening on the farms to the south, which fall outside the greenbelt in an area Empringham said is likely to become subdivisions at some point.

Developers in the region have a very different outlook. They are concerned the ministry isn’t considering pre-existing infrastructure and development approvals as it moves through the process of establishing an agricultural system.

“Remember 90 per cent of the housing that’s built is built by the private sector, so . . . if you want to provide that supply, the industry needs to have some certainty, not just in the future, but also some certainty with the approvals they currently have,” said Joe Vaccaro, CEO of the Ontario Home Builders’ Association.

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs said the government is committed to managing growth, while protecting Ontario’s farmland and supporting economic viability.

The development of the agricultural system, which stems from the co-ordinated review of four land use plans and was recommended by the review panel chaired by David Crombie, is still in its early stages.

The provincial government has developed a draft map of the agricultural system, showing proposed protection boundaries as well as existing infrastructure and services.

The draft system map and implementation procedures are out for public consultation until Oct. 4. This concerns Empringham, who notes the summer and fall are a busy time for farmers.

For those that can spare two-and-half hours, there’s an online webinar, provided by the ministry, on Sept. 6, on the mapping and implementation procedures, for members of the agricultural community.

Once the public consultation is closed, the government will move forward with plans to update the map by the end of this year. Municipalities will have a couple years to refine it as part of their official plan reviews, which are required by July 2022.

Down the road, Horner, who is also a Mulmur Township councillor, expects there could be challenges between municipalities and the province over which lands should be protected for agriculture and which should be open to development.