New report shows that Toronto is not so bad compared to world cities

Nearly three in five people say they can’t afford to buy a house where they live.

www.ipsos.com

Can you afford to buy a house? Most say they're priced out of the market

Nearly three in five people say they can’t afford to buy a house where they live.

4 November 2019

Toronto-area insurance broker Nicole Barbosa says she’s been thinking about trying to buy a house for the past year.

Her biggest hurdle: affordability.

The 33-year-old has been renting a basement apartment with her boyfriend for almost two years, but already knows she won’t be able to buy a home in the area where she lives west of the city, which is close to work and family.

“I’m hoping that our situation will improve when it comes to affordability. However, unless we make huge changes to our budget and lifestyle, that will likely not happen,” says Barbosa.

“If something doesn’t give and we are getting to the point where we are fed up, then it’s going to have to be either pick up a second job or really go somewhere where we might not be as happy as if we lived closer to home.”

Barbosa adds that it doesn’t make sense to her that most people that she knows who want to buy a home can’t afford one.

The average price of a home in the Greater Toronto Area has more than doubled ̶ increasing more than 110% over the last nine years ̶ according to the Canadian Real Estate Association. Meanwhile, median household income in the city increased by less than 5% in the 10-year period from 2005 to 2015, according to the latest government census data.

It’s a similar story in many of the world’s thriving urban centers.

A combination of low interest rates, a growing population, restricted housing supply and foreign buyers have pushed house prices beyond the reach of many ̶ especially first-time homebuyers ̶ as incomes have not increased at such a rapid pace.

In a new

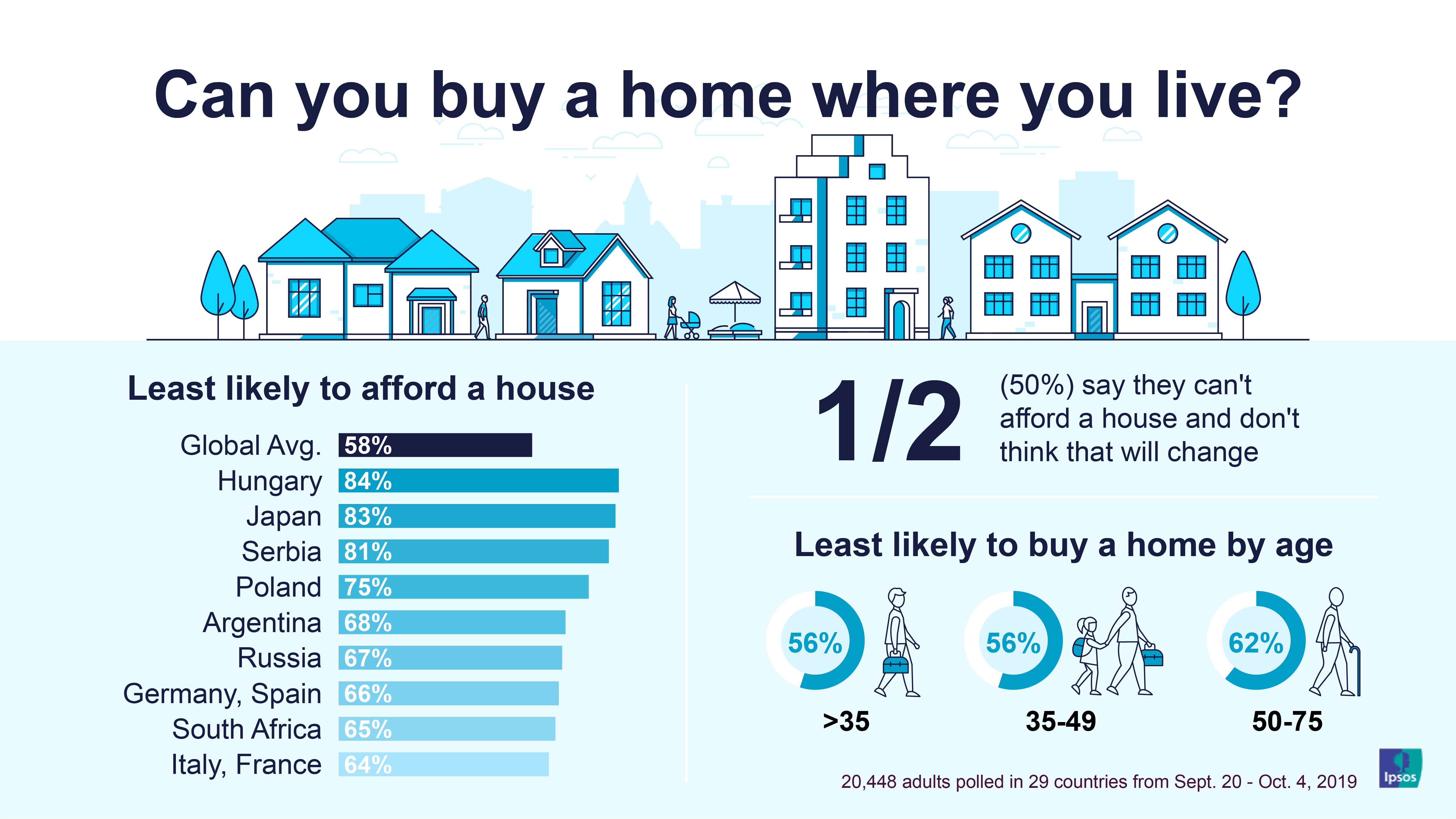

Global Advisor survey of more than 20,000 people across 29 countries, nearly three in five people (58%) say it is unlikely that they can afford to buy a home in their local market.

The top countries where most said they were priced out of the market were Hungary (84%), Japan (83%), Poland (75%), Argentina (68%) and Russia (67%). Seven of the top 10 countries are in Europe.

Lack of affordability a sign of success?

Toronto-based Doug Porter, Chief Economist at BMO Financial Group, says this list reflects nations that are either characterized by tough economic backdrops and resulting low incomes as in the case of Russia and Argentina, or are densely populated like Japan and Germany with traditionally high home prices versus incomes.

“I think the broad-based nature of this list just shows how widespread this issue is; even as interest rates have come down over the years, home prices have simply vaulted higher in response,” says Porter.

“Almost everyone wants the best living conditions possible, and prices will almost always be driven right up to the edge of what people can afford and sometimes even above the edge.”

How affordable you think property is in your market in 1 minute:

Porter adds that this is especially true when confidence is high, consumer sentiment is generally strong and jobless rates are down – meaning the lack of affordability in housing can be a sign of the price of economic success.

“Classic example is Silicon Valley; a booming economy, but some of the worst affordability issues in the world,” says Porter. “Of course, supply constraints can also be an issue, especially in densely populated and relatively wealthy nations like Germany and Japan and yes, San Francisco or even Vancouver.”

The median price of a single family home in the San Francisco Bay Area has more than doubled in the last 10 years – up 105% from September 2009 to 2019, according to data from the California Association of Realtors.

Out of the top 10 countries where the most people said they can afford to buy a home, seven were emerging markets.

- China (74%)

- India (73%)

- Saudi Arabia (61%)

- U.S. and Peru (55%)

London-based Chris Hale, Director at Ipsos MORI’s Social Research Institute, says this could suggest that house price to income ratios are more favourable in emerging markets.

“Economic growth rates are more rapid in emerging markets than in developed markets, so that might be part of the story,” says Hale.

Avi Friedman, Professor of Architecture at Montreal’s McGill University, agreed adding the affordability gap – the gap between the cost of housing and income – maybe be less, making buying a home more attainable in emerging markets.

Of those respondents who said it’s unlikely they can afford to buy a home, more people in emerging markets said this was a temporary situation that could improve in the future ̶ with Peru (80%), Brazil (79%), Argentina (78%), Mexico (75%), Saudi Arabia (73%) and India (72%) at the top of the list.

Buying less of a house

Still Gary Painter, Professor in Sol Price School of Public Policy at University of Southern California, says what’s changed is the increase in housing cost burdens as defined by the percentage of household income that is dedicated to rents or other housing costs. This means it’s costing us more to pay for how we live.

In Canada, the cost of owning a home in the country’s two largest cities – Toronto is 79% of median household income, and 88% of median household income in Vancouver ̶ according to a report from RBC Economic Research.

Prof. Friedman says people are still buying homes, but it may be “less home” than in previous generations.

“In most of the world’s capitals there is the phenomenon of microunits in order to cope with the affordability gap. What you see across the board is that developers have now shrunk the typical unit sizes,” says Prof. Friedman.

“You can still buy a home but you can buy less of it. This will be the equivalent of less than 50 m² where people start their life, work hard, and then they hope to switch into a larger place.”

Barbosa, however, says she rather rent until she can find something in her area that she thinks is worth the value.

“I don’t want to be house rich and then gas poor, because I’ve got to drive an hour to see our parents,” she says. “From what I’ve seen house-hunting, the value of what you get doesn’t seem worth it for me at this point.”