In the early evening of May 12, 1955, a train pulled out of Lower Manhattan’s Chatham Square, near City Hall, bound for upper Manhattan and the Bronx via Third Avenue. It was the last run of the Third Avenue elevated, and the last time a train ran up a large chunk of Manhattan east of Lexington Avenue for six decades.

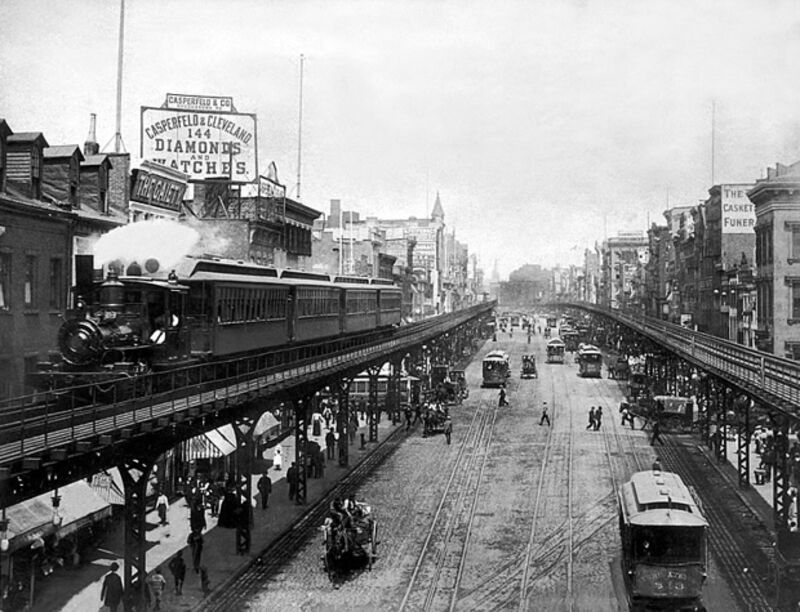

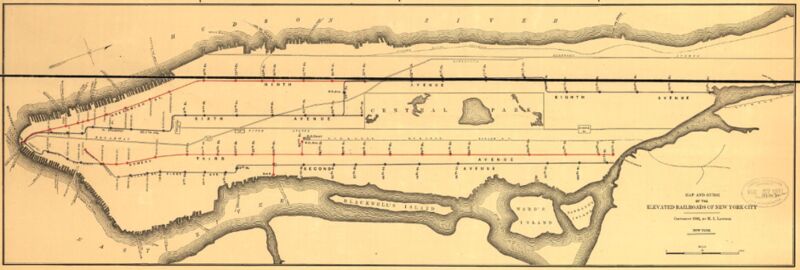

The Third Avenue elevated—like lines along Ninth, Sixth, and yes, Second Avenues—predated the subway. The line opened in 1878, with service from South Ferry in Lower Manhattan to 129th Street in Harlem. Other elevated, or “el” lines came into service at around the same time. The Second Avenue elevated, which ran from City Hall to Harlem for most of its life, operated from 1875 to 1942. The Ninth Avenue elevated, the first el, operated from 1868 to 1940. The Sixth Avenue elevated was constructed in segments during the 1870s and ceased operations in 1938.

End of the Els

It’s not a coincidence that all of these lines stopped running at around the same time.

“The els were loud, dirty, messy and slow,” says Clifton Hood, a professor of history at Hobart and William Smith Colleges and author of

722 Miles, a history of New York City’s subway system. “The subways were modern and the els looked bad.” The city government, often backed by real-estate interests (and with an eye towards real-estate tax receipts), was happy to remove them.

“The els were run by monopolistic companies that provided bad service,” Hood says. The

IND subway system, a municipally-operated service, was designed in many instances to compete with companies running existing rapid transit lines—both subways and els. “One purpose of the IND was to compete with particular el lines,” Hood says. “That was the idea of the Sixth and Eighth Avenue lines.”

There were, of course, many who opposed removing elevated lines, especially on the subway-poor East Side. According to a

blog post from CUNY’s Gotham Center for New York City History, “skeptics questioned the wisdom of summarily displacing the 25,000,000 the Third Avenue El had carried in 1954. Some lawmakers tried to ensure that El service would not be eliminated until construction of the promised new subway began.”

Was another way possible? Would some alternative to the Lexington Avenue line—which

carries more passengers by itself than the entire networks of San Francisco, Chicago and Boston—be better than none at all? It’s hard to say.