Based on everything I know, 5-hour Montreal-Toronto travel times, even with frequent service, won't boost ridership much without significantly higher fare subsidies than today. Thus making me wonder if the sudden appearance of the by-pass is because of institutional concerns. Though if it only saves half-an-hour or less, as we discussed above, I still doubt it's enough.

Every analysis can only be as relevant as the data from which it is derived is: You seem to base your entire line of argument on the financial figures which are provided in VIA's Annual Reports and these indeed show for its Corridor services a per-passenger subsidy of $30 per passenger pre-pandemic:

Source: VIA Rail Annual Report 2019 (p.9)

So, clearly, if VIA already loses $30 per passenger, then it stands to bleed even more taxpayer money when increasing its services, unless the utility it provides to its passengers increases on a scale which can only be achieved by cutting at least one, if not: almost two hours from the journey time between Montreal and Toronto, right? It's notoriously difficult to predict the future, even more so if you don't have access to VIA's internal data, but let's use the little data that

is readily available. Therefore, given that VIA expanded its Corridor services steadily in the 5 years leading to the pandemic, we should expect that its operating costs have increased considerably.

Well, let's have a look at what happened between 2014 and 2019. As train-mileage increased in the Corridor by 16.5%, passenger-miles increased by 22.4%, passenger counts by 34.1% and revenues by even 49% (or still 37.4%, after adjusting for inflation). At the same time, costs increased by

15.3% 20.4%, which shrinks to only

6.2% 11.0% once you adjust it for inflation:

The above table shows that for every percentage point increase of

train mileage in the Corridor,

ridership increased by 2.1% and

revenues (adjusted for inflation) by 2.3%, while

costs only rose by

0.4% 0.7% and the

deficit decreased by

2% 1.4%. At the same time, it shows that two factors were certainly not responsible for this surge in ridership:

travel times (which increased by 2.9% for average travel times and 5.6% for minimum travel times) and

on-time performance (which slipped by 8 percentage-points).

The reason why the figures you are apparently using fail to explain VIA's performance between 2014 and 2019 is that you seemingly struggle to understand the differences between Management Accounting reporting and Financial Accounting reporting, which is summarized below:

Management accounting is a field of accounting that analyzes and provides cost information to the internal management for the purposes of planning, controlling and decision making.

[...]

Managerial accounting is concerned with providing information to managers i.e. people inside an organization who direct and control its operations. In contrast, financial accounting is concerned with providing information to stockholders, creditors, and others who are outside an organization. Managerial accounting provides the essential data with which organizations are actually run. Financial accounting provides the scorecard by which a company’s past performance is judged.

What's the difference between Financial Accounting and Management Accounting? Management accounting is a field of accounting that analyzes and provides cost information to the internal management for the purposes of planning, controlling and decision making. Management accounting refers to...

www.diffen.com

In short, Financial Accounting reports (like the tables from VIA's Annual Report) concern the past performance and provide answers for questions like "How much did VIA cost the taxpayer last year?". Conversely, Management Accounting reports inform decisions by answering questions like: "If we expanded our Montreal-Ottawa service next year, would our operating deficit increase or decrease?". Unfortunately, Managerial Accounting reports are notoriously difficult to obtain as they are generally considered commercially sensitive (ask the poor guy who has tried to obtain VIA's HFR studies through an Access-to-Information request!).

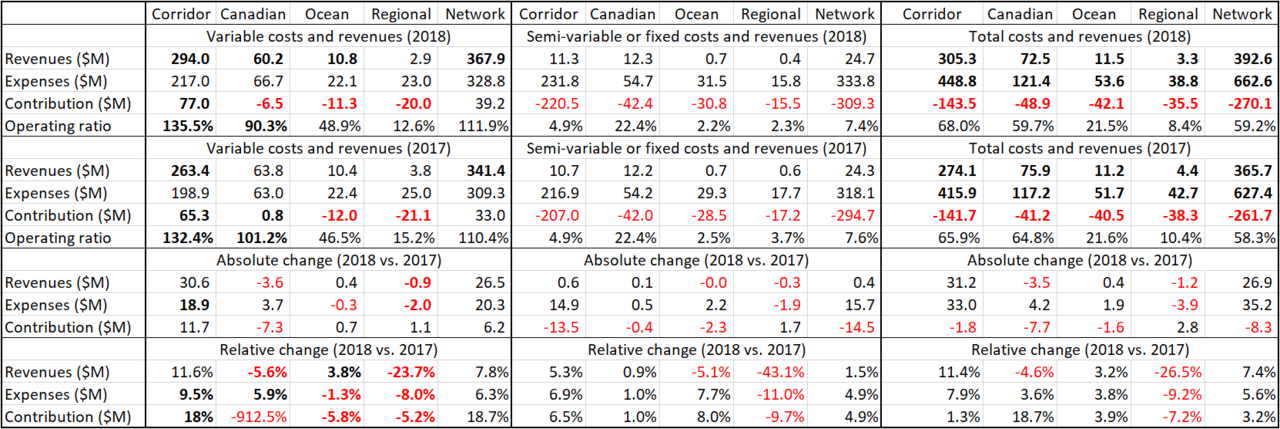

Nevertheless, given that one of the most central differences between both philosophies is the treatment of overhead and other fixed costs (Financial Accounting seeks to somehow allocate them across the various activities in the least arbitrary way possible, whereas Management Accounting ignores them as "sunk costs" which remain unchanged by whichever change in the output of the activities is studied), we can use the one report in which VIA actually separates the direct costs and revenues from its indirect costs and revenues. These figures, published in its Corporate Plans rather than its Annual Reports, show us that VIA's Corridor services actually recover 135.5% of their direct operating costs, which allowed it to contribute $77 million towards VIA's massive overhead costs, thus reducing its burden to the taxpayer by that same amount. Therefore, VIA's Corridor services generate a positive cashflow of $17 per passenger [$77.0 million / 4,782,493 passengers in 2018], rather than making it lose $30 or whatever figure you were looking at:

Compiled from:

VIA Rail's Summary of the Corporate Plan and

Annual Plans 2017 and 2018

Note: Re-post from

post #6,707

***

With all of that said, what's the implication here? The only thing which holds VIA's Corridor services in the red is the massive amount of overheads and other non-direct costs it absorbs. The growth path shown between 2014 and 2019 demonstrates that there clearly is a way for VIA to outgrow its non-direct costs by increasing its services further - without the need for massively reducing its travel times at a great expense. All it needs is the infrastructure access and fleet to do so - and these are exactly the gaps which HFR would fill...

Have a good night!

Update (2021-12-16): I've corrected a mistake in my table, which understated VIA's costs (and thus also: deficit) in 2019 by $20 million, which led to a few minor corrections in the text, as shown above....