It’s been hard to resist starting every post focusing on the MTA’s current ridership situation and budget woes with the sentence, “It’s been a rough few months for transit,” but it’s been a rough few months for transit. Often associated with the hoi polloi and dirty masses, most transit systems didn’t have reputations for cleanliness before the pandemic and whether fairly or not, quickly become associated with the spread of disease as the pandemic descended on the world.

After a spring in which a spurious MIT study that relied heavily on a correlation/causation error drove the conversation, a group of pro-transit researchers are fighting back, and in a new study released by the American Public Transportation Association, they report no known links between coronavirus cases and public transit.

“As of August 2020, no outbreaks have been traced to public transit in the United States,” the report, authored by New York’s own Sam Schwartz, said. “Based on our data review of case rates and transit usage in domestic cities, the correlation between infection rates and transit usage is weak or non-existent.”

Schwartz’s survey of current pandemic experiences is part of a larger report on transit-related best practices for the COVID-19 era, and you can access the report

here as a PDF. It’s very much yet another attempt to change the narrative. The MIT study came out early in April, and despite debunking by

Alon Levy and

Aaron Gordon, two well-respected voices within the transit community, it set the stage for months of American fears over transit.

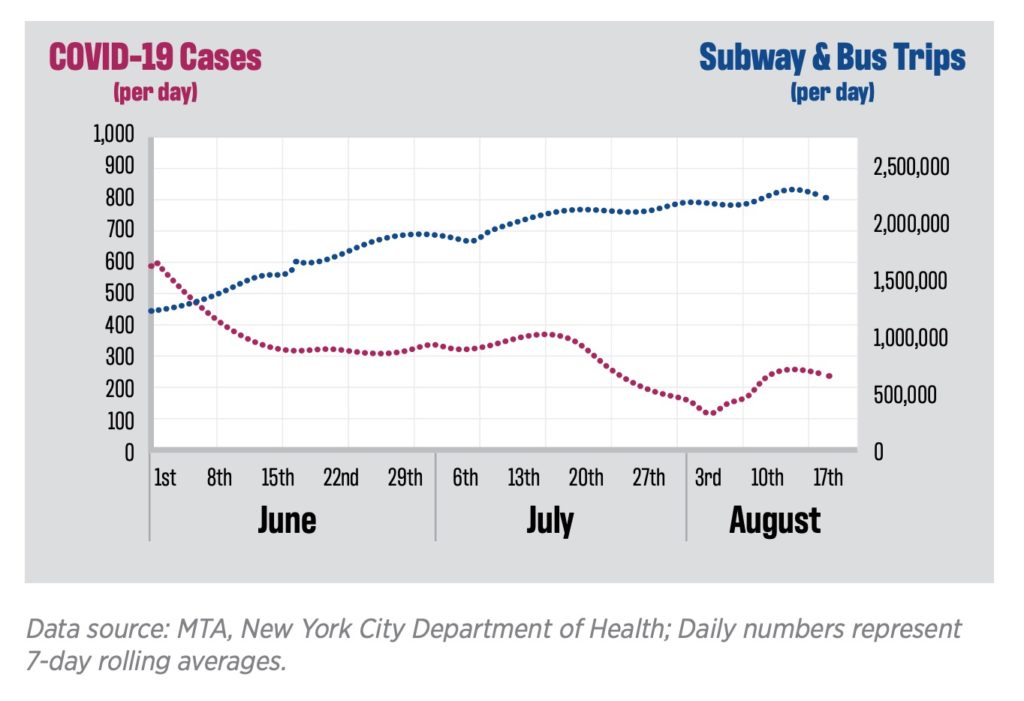

Nearly immediately, many one-time transit riders relied upon the MIT study to reinforce ideas that transit isn’t safe and is a source of spread. Even now, seven months after New York started working from home en masse, subway ridership is only around 1.7-1.8 million per day, approximately 30% of normal, and many New Yorkers have said their commute is the biggest barrier to returning to work. The problem is one of psychology and one of science. I understand why people may be hesitant to ride the subway or hop a bus where they may have less control over everyone around them, but sitting in a poorly ventilated office with other people for 8-10 hours a day is more dangerous than the ride shorter to get there. Schwartz is trying to prove it.

Schwartz has to overcome the challenges of proving a negative, and he makes a compelling case. He looks at transit agencies large and small, from NYC to Hartford to the Quad Cities to Northern Kentucky. In each case, after lockdowns eased, increased transit ridership hasn’t corresponded to an uptick in coronavirus cases. Since the spring at least, when mask mandates were instituted and social distancing became the norm, careful transit usage coupled with disinfectant procedures haven’t led to an uptick in positive tests. Here’s Schwartz’s conclusion: