Dan416

Senior Member

Some of those new LRVs we need on Eglinton. Others are needed to replace the legacy network. How many vehicles are left after those things?

Some of those new LRVs we need on Eglinton. Others are needed to replace the legacy network. How many vehicles are left after those things?

Tramway Considerations for Montréal’s Birthday

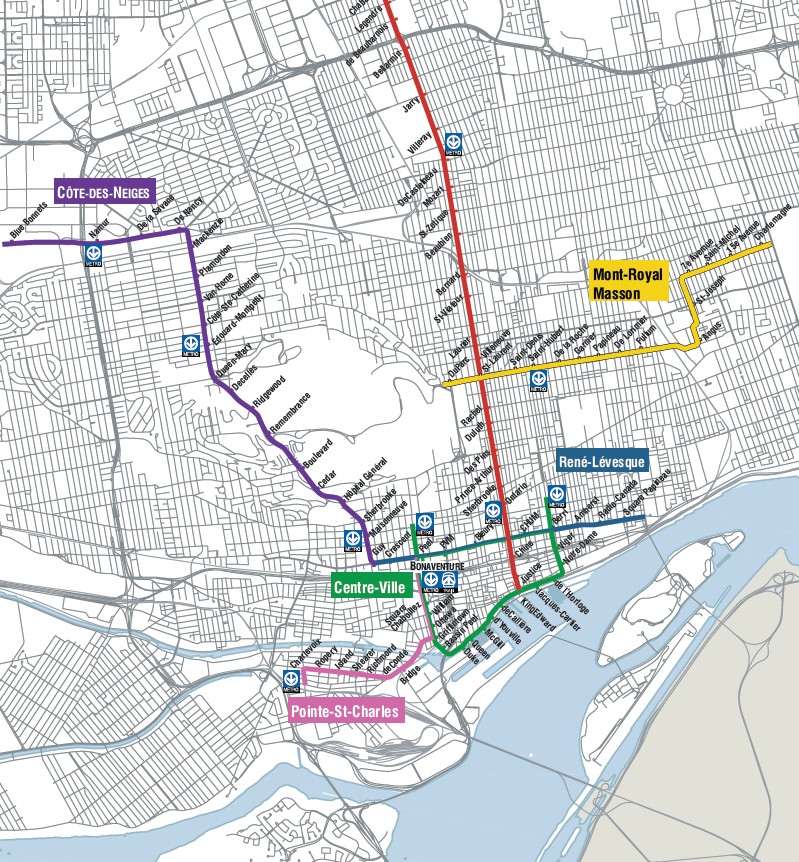

So it looks like Richard Bergeron has his own ideas concerning our city’s 375th Anniversary, and has proposed 37.5 km of new tram routes ready-to-go by 2017. Apparently, a finance working group has been established, though precisely what this means is anyone’s guess. I would normally be more optimistic, but there’s a new cynic growing somewheres deep down inside me.

Bergeron has earned himself (somehow) a reputation as being something of a ‘tram nut’ (this is how he’s been reduced before – modern media can suck in its efforts to be overly personable). Back in the day, a more optimistic Bergeron was keen on a 250km, $20 billion tram system to cover most of the densely packed urban core of Montréal. If this seems like a lot of tramways, consider that as recently as 1959 we had about 378km worth of tram line throughout the city and some first and second ring suburbs. This was unceremoniously dismantled in `59 largely out of pressure from the American automobile industry (see Great American Streetcar Scandal).

Another recent proposal came about as part of a larger metropolitan transit plan, this time in 2008-2009, when Mayor Tremblay announced a far less ambitious plan of three lines of 20km. That plan was supposed to be complete by 2013.

Something tells me we’re not going to meet that deadline.

That said, Bergeron is persistent and (hopefully) involved in the new plan, though I wonder why not shoot for something far more complete, such as 375 kilometer’s worth. I suppose 37.5km will cause enough traffic headaches for the next six years, especially given how slowly and inefficiently we build these days. But no matter which way you cut it, this is something we desperately, definitely need.

That said, there are some key considerations we need to discuss.

For one, trams or trolleys? Are steel wheels on rails necessarily the better way to go? Or can rubber tyres provide a sensible alternative, better able to climb steep gradients? Rails will undeniably work better insofar as the tram lane is segregated from regular traffic, especially on long straight streets, such as Boul. René-Lévesque. However, climbing up Cote-des-Neiges road or Atwater might be better handled by a rubber tyre alternative. And consider as well that there are models that feature both steel wheels and rubber tyres, and can switch between.

Second, who will run this new transit system? Ideally, the STM runs the tram network as well as the buses and Métro, and as Bergeron has planned, the proposal is designed to intersect with existing Métro stations. A common fare and transfer system seems like a no-brainer, but this needs to be planned from the outset. The last thing we want is an expensive tram that requires a separate fare. This could be enough to kill the system entirely.

Third, will installing the system be enough to get people to give up on using their cars? Probably not without an expensive and effective mass media campaign and municipal bylaws regulating when cars can enter the city (however the city decides to define this is really up to them). In effect, this system may prove itself far more useful, if not overtly desired by the citizens, if we go so far so as to actually employ measures to keep people from driving their cars. Offering excellent service and clean trams is one way, convincing the citizenry they have a fundamental responsibility to each other to use public transit is an entirely different measure.

Fourth, and related to the aforementioned points, it may be wise to install trams on streets we intend to be new pedestrian axes – such as Ste-Catherine’s. Though business associations perpetually live in fear of street closures, road work and any other threat to the overwhelming predominance of motor vehicles on our city streets, the fact is that cities larger than our own have been able to mitigate environmental damage from mass automobile use by offering excellent public transit, with trams playing a vital role ferrying people quickly between the urban core and the first ring suburbs. I would not use Toronto as a model, incidentally, when there are so many European and other American examples to go by.

Point is if City Hall wants to really make this work, they have to provide an alternative they can enforce to the point where few will question the logic. That anyone today can feel justified in arguing against capital investment in new public transit initiatives is, in my honest opinion, a measure of our stubborn regressiveness. We need to exercise this demon from our collective conscience.

We simply can no longer afford not spending money on massive public transit projects. Furthermore, we need to grow some local government sack and start finding ways of compelling people to give up on the selfish act of using a car when cheaper, cleaner alternatives exist.

Three other American cities in addition to DC will open new streetcar lines this year, and at least 12 more cities are expected to advance construction on lines that will open later.

The four lines expected to open in 2014 are in DC, Tucson, Seattle, and Atlanta.

Tucson’s Sun Link streetcar will be the first modern rail transit to open in that city.

Seattle’s First Hill streetcar will run next to a cycletrack for much of its length, in an impressive multimodal layout.

Atlanta’s downtown streetcar will be the first modern streetcar to open in the US that doesn’t use the ubiquitous 66′ long streetcar model first popularized in Portland. Instead, Atlanta will use a 79′ long tram similar to the light rail cars in Norfolk.

North of the border, Toronto will shortly begin to use new 99′ long trams on its expansive streetcar network, the largest in North America.

Even more cities will begin construction or continue construction on new lines that won’t open until 2015 or later. They include Charlotte, Cincinnati, Dallas, Detroit, Fort Lauderdale, Kansas City, Milwaukee, New Orleans, Oklahoma City, Tempe, San Antonio, and Saint Louis.

Many other cities, including Arlington, have streetcars that aren’t expected to begin construction yet, but aren’t far behind.

Streetcars are back in the U.S. in a big way. Inspired by the Portland Streetcar, and helped along by federal programs like New Starts and TIGER, cities across the United States are breaking ground and beginning service on modern streetcar systems.

It will be interesting to see what kind of impact these streetcars have on transit and urban development in these cities, especially the smaller ones that haven’t had any rail for decades.

Elsewhere on the Network today: Missouri Bicycle Federation shares the news that Jerry Seinfeld really likes to walk or bike to work. Cyclelicious speaks with a leading bike advocate about the importance of social media in uniting people around the cause. And Parksify shares a great adaptive reuse idea from New York City: transforming a parking lot into an ice skating rink.

There's a big difference in purpose between the Toronto streetcar routes and those new US systems.

Toronto streetcar lines are major surface transit routes. They run long distances down the length of streets, similar to buses and their primary purpose is to move people from one part of the city (or street) to another.

The new US systems are downtown revitalization schemes, similar to streetscape improvements, public squares and major landmarks.

If you look at their size and configuration (they're often one way loops that make many left turns and hardly leave small downtown cores), they don't really serve much of a transit purpose beyond acting as very short distance circulators. In many cases they aren't much faster than walking. I used to think these were frivolous wastes, but I've warmed up to them a bit in recent years, and think they have a purpose in making a downtown area more aesthetically pleasing and spatially defined. Those are important things in their own right - Toronto could certainly stand to have its public realm made more attractive - but we should never confuse these US streetcars as being real transportation improvements.

Toronto streetcars, generally, run much, much more frequent and carry much, much more passengers. For example, the 510 Spadina streetcar runs more frequently on Sunday afternoon than most US bus routes during their rush hours.

There's a big difference in purpose between the Toronto streetcar routes and those new US systems.

Toronto streetcar lines are major surface transit routes. They run long distances down the length of streets, similar to buses and their primary purpose is to move people from one part of the city (or street) to another.

The new US systems are downtown revitalization schemes, similar to streetscape improvements, public squares and major landmarks.

If you look at their size and configuration (they're often one way loops that make many left turns and hardly leave small downtown cores), they don't really serve much of a transit purpose beyond acting as very short distance circulators. In many cases they aren't much faster than walking. I used to think these were frivolous wastes, but I've warmed up to them a bit in recent years, and think they have a purpose in making a downtown area more aesthetically pleasing and spatially defined. Those are important things in their own right - Toronto could certainly stand to have its public realm made more attractive - but we should never confuse these US streetcars as being real transportation improvements.

US streetcars tend to be downtown circulators, think people mover in Detroit.

US streetcars tend to be downtown circulators, think people mover in Detroit.

The Mover costs $12 million annually in city and state subsidies to run.[9] The cost-effectiveness of the Mover has drawn criticism.[10] In every year between 1997 and 2006, the cost per passenger mile exceeded $3, and was $4.26 in 2009,[11] compared with Detroit bus routes that operate at $0.82[11] (the New York City Subway operates at $0.30 per passenger mile). The Mackinac Center for Public Policy also charges that the system does not benefit locals, pointing out that fewer than 30% of the riders are Detroit residents and that Saturday ridership (likely out-of-towners) dwarfs that of weekday usage.[9] The system was designed to move up to 15 million riders a year. In 2008 it served approximately 2 million riders. In fiscal year 1999-2000 the city was spending $3 for every $0.50 rider fare, according to The Detroit News. In 2006, the Mover filled less than 10 percent of its seats.[9]

Among the busiest periods was the five days around the 2006 Super Bowl XL, when 215,910 patrons used the service.[12] In 2008, the system moved about 7,500 people per day, about 2.5 percent of its daily peak capacity of 288,000.[13][14]