The first of a two-part interview with Sam Crignano of sister companies Cityzen and Dominus Construction Group. Part two follows next Thursday.

Sitting on the 32nd floor terrace of London on the Espanade, UrbanToronto sat down with Sam Crignano to talk about the company's background, Absolute World, L Tower, Backstage, Pier 27, 154 Front Street East, as well as Cityzen's recently acquired waterfront site near Cherry Street, and what else the future may hold.

Sam Crignano on the rooftop terrace at London on the Esplanade. Image by Craig White.

Sam Crignano on the rooftop terrace at London on the Esplanade. Image by Craig White.

How did you get started in the development industry?

It started back in the days when my father would take me on weekend excursions looking at parcels of land. My father was a carpenter by trade, so he and my uncle would buy parcels of land, but he would also acquire homes that he would renovate and resell. That's what got me interested in real estate. Then in 1984 when I was first married, my father-in-law was involved in a construction company, and also a participant in Camrost. He and I got together and we decided to set up a company mainly involved with land development. We were involved in the Vaughan Business Park, and another development which was initially commercial/industrial called The Crossroads at Langstaff and Dufferin, but which ultimately became residential. Throughout the 80s we were mainly involved in Camrost. Then in the early 90s when the great recession came - because we had a construction arm - we needed to find something else to do other than build luxury condominiums because that market had collapsed. The recession coincided with the election of the new NDP provincial government and to stimulate the economy they introduced all sorts of new initiatives with respect to affordable housing. We quickly got involved in non-profit housing, and we that until 1995 when the Conservatives came to office and axed those programs. At that point we decided we needed to redirect the company, and the decision was made to get back into high-rise condominiums. I came across a property that had been assembled at 55 Bloor Street East, and that was our first residential condominium project after the great recession. That was in 1997, and then I wanted to grow the company through partnering with other companies, but my father-in-law wasn't interested in expanding the company at that rate.

Was it the two of you at the time who were partners?

Yes, so I decided at that point to start a new company. That was Cityzen back in 2000. Our first project out of the gate was Hemingway, at The Donway West and Lawrence. While that was happening, I was approached by one of the partners at Fernbrook who had tied up a site in Brampton. I looked at it, and at the time they showed interested in getting involved in high-rise. I didn't quite like that site in Brampton, and because I needed a partner for Mississauga, I introduced them to the Mississauga site. They were quick to like it, and that formed that new partnership. The Absolute project was my first co-venture with Fernbrook Homes. While that was going on, we acquired this site here downtown [London on the Explanade], so with Fernbrook, we continued to grow. We acquired the Bloorview Children's Hospital in North York, and shortly thereafter we acquired two sites in Oakville: one on the waterfront at the foot of Bronte called The Shores, and another one at Dundas and 6th line where in the last few years we have launched the first phases of Waterlilies in the form of stacked townhouses. Then we were presented with opportunities down in Central Toronto, and the first one was Pier 27. I got the call from another partner of mine on the Pier 27 project, his name is Gerry Goldenberg. There was a relationship between Goldenberg and the Roth family and they had interests in this property. After twentysome odd years of battling with the City, they finally got an approval at the OMB, and that's when I was called in and we cut the deal to acquire Pier 27. Obviously I needed partners to do that deal. With Fernbrook we already had an understanding, and because of the close proximity of it to this project [London on the Esplanade] I felt an obligation to invite the Cheungs to participate in that project. That's what started that new relationship with Cityzen, Fernbrook, and the Cheung family. Shortly thereafter we were presented with the L Tower project, and then Backstage, and it just evolved from project to project. I think in total now we're involved in 14 different projects, and we're approaching 10,000 units in total that we have under development.

Most of your immediate family is involved in the business as well. What's it like operating a family business on this scale?

[laughs] It's not easy, it's not easy. My wife has been with me ever since we started the company. Sara was at U of T, and after that she wanted a change so she joined us, initially in customer care and also helping facilitate colour selection. About a year and a half ago she transitioned into heading up our marketing department. My son works for us in the summer. He's at Pier 27 working for our sister company Dominus, but he's still at school so we'll see what the future holds for him. My youngest daughter for the first time this year decided that she was going to work the summer, and was at Absolute in customer care. Not always easy.

There's an interesting story about how you came to decide on holding a major international competition for the Absolute World design. For our readers, could you recount the story for us?

I was golfing, and in my foursome there was Ed Sajecki, the Planning Commissioner of the City of Mississauga. We were playing in a tournament - I'm not a big golf fan mind you! - we were talking about different things, and I wanted to broach the subject of that corner site that we owned. At that point we were in the middle of our third phase, and we left those two sites on Hurontario for the last. The reason for that was we always knew that intersection was important. In terms of Mississauga, it's where main street meets main street, and we were never quite sure what we wanted to do there. The idea of a hotel was thrown about. At one time there was even the thought that there would be an office component, so I was talking mainly about height and what he thought was appropriate. I said to him 'you know, I think a tall building is appropriate for that corner', and without any consideration I said 'maybe something 50 storeys or higher', and he didn't dismiss it, saying 'we could probably consider something like that', and then just out of the blue I said 'maybe we should hold an international design competition', and he looks at me and goes 'you would do that?' [laughs], and I said 'sure' without really knowing what's involved. So we continued our golf game and that afternoon he went back to the office and had a conversation with Hazel McCallion. Shortly thereafter he calls me and he sais 'Okay Sam, let's do it', and I say to him 'do what?' [laughs]. He goes, 'this competition, it's a great idea, we love it'!

Sam Crignano and interviewer Dumitru Onceanu on the rooftop terrace at London on the Esplanade. Image by Craig White.

Sam Crignano and interviewer Dumitru Onceanu on the rooftop terrace at London on the Esplanade. Image by Craig White.

So that's how it all began. I then called Roy Varacalli and I explained to Roy that we wanted to engage in this competition. At first he thought it was a crazy idea and that we shouldn't do it, but he quickly caught on. We ended up hiring a firm that specialized in facilitating these competitions. From day one we decided that this was not a closed competition where we hand-picked the architects. We wanted to make this available to anyone and everyone, and the first thing we did was create a website to announce it and spread the word. We had a registration page, and it didn't take long for the list to grow to 600 firms from all over the world who showed interest in this competition.

Far more than you could have expected?

I never believed that we would get that many, but what really surprised me was the fact that we received 92 submissions. Some of these submissions came from universities where the architecture professor got together with some students and they made submissions, but most of them were established firms. It was amazing what we received: scale models, AV presentations. Some of these designs were well developed, approaching working drawings.

Was there anything really off the wall that you received?

Oh yes, a lot of weird and strange designs: there was this one that was this exoskeletal thing that looked like it was from another planet.

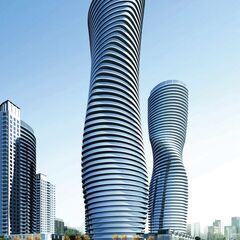

The difficulty was in shortlisting; I believe it was 5 or 6 that we shortlisted. We had assembled a jury that was well represented in terms of people from industry, but we had so many submissions to choose from. We wanted some local representation as well, and it was difficult picking the local firm that we wanted to participate. We ended up going with Quadrangle. They came up with a cube-like design which was interesting. From the very beginning when the press got hold of these images, it was almost like they all got together and said 'ok this is the one that we're all gonna publish' because they all picked the same one, that curved design from MAD. The Globe, The Star, they all went with that same image. It was so different from everything else, and to a point where there were a lot of people who never believed that you could actually build it.

So you had a winner early on?

Well we had a design that people liked. We held a series of exhibitions where we presented these five shortlisted designs, and what was amazing to me - because I would be the mystery shopper in the background just listening to what people had to say - was that no one spoke about height. No one ever said 'these buildings are too tall', or asked what the height of these buildings were. They were all focused on whether they were round, or how that cube-shaped one all came together. They were focused on all these elements other than height. When you looked at them, the designs were all nice so the height was appropriate for that design.

Suddenly when you have stellar design, height doesn't figure into the conversation as much?

Height just went away. That was a surprise, and initially it was difficult for us because the initial design that was presented had a twisting structure - the winning design now - and that was a problem because of cost. What happened was that they quickly got together with local consultants. Roy Varacalli - our local architect - was at the table as well and it took a while but they came up with this ingenious approach. Effectively what gives that building its shape isn't the structure itself, it's the slab edge. They were able to come up with a design that just by articulating that slab edge was enough to give it the shape that we needed. Basically each floor is the same shape. It's an elliptical shape, and that's another mystery. People think that it's all different, but it's just the rotation of that elliptical shape, and once you get to the centre of the building it mirrors at the top, and so that reduced the number of layouts. We still ended up with some 70 different layouts.

Looking down on Absolute World, showing rotated elliptical floor plates. Image by Jasonzed.

Looking down on Absolute World, showing rotated elliptical floor plates. Image by Jasonzed.

Looking up at Absolute World, showing rotated elliptical floor plates. Image by Jasonzed.

Looking up at Absolute World, showing rotated elliptical floor plates. Image by Jasonzed.

Looking up at Absolute World, showing rotated elliptical floor plates. Image by Jasonzed.

Looking up at Absolute World, showing rotated elliptical floor plates. Image by Jasonzed.

Looking up at Absolute World, showing rotated elliptical floor plates. Image by Jasonzed.

Looking up at Absolute World, showing rotated elliptical floor plates. Image by Jasonzed.

Tell us about the economics of building irregular space. Some developers generally avoid straying too far from rectangular floor plates. The twisted form here really adds a lot pressure on the interior space to adapt from one floor to another. How did Cityzen find that experience, and in what ways did you have to change your approach to building construction?

Clearly it took more money to build. It took a lot more to design it. When you're doing something that's not conventional, there's always a margin of error that everyone builds in, so clearly it was more money, and we sold for more money. The revenues outweighed the additional costs. I'm still a firm believer that great design sells, and not only does it sell but it sells at a premium. It costs more money to create it, but in the end you get it back. We have the same issue at L Tower. We have that articulating north facade which created all these different layouts. It's just something that you have to pay more attention too, and the documentation has to as well because at the end of the day you have to deliver what you sell. In all our buildings, you could build a point tower that's 8000/9000 sq ft that yields 10 units per floor. So basically 10 different floor plans in all. I don't think I've ever built a building in my life that only had 10 different floor plans. From day one we've always played with different unit types and layouts and designs.

This project was one of MAD Architect's first major commissions, their first international project, and the first landmark design competition ever won by a Chinese architect. How was it like working with Yansong Ma?

At the time he was a small boutique. I think it was Yansong and two other partners, but you have to understand one thing about Yansong - I don't know if you know his history, do you know where he trained?

Wasn't it Yale?

He went to Yale - but after school he trained with Zaha Haddid, and to some degree you see some of that influence. I don't know if you're familiar with her work, there was an exhibit a few years back at the Guggenheim in New York where they featured all of her work. The whole Guggenheim was Zaha Haddid.

At that time wasn't it all unbuilt? It took her a long time didn't it?

It took her - I don't know - she was 50 years old before she got her first commission. Amazing that she was able to sustain herself that long. But she goes through this process when she designs. She starts with painting and that painting eventually manifests itself into a design form, and she uses all kinds of different elements. She produces scale models. She'll paint, she'll use plastic, she'll use glass, she'll use steel, all these influences. Her designs are radical to some degree, but interesting. So I think that was his [Yansong's] influence. If you speak to him, he'll tell you that more often than not he's inspired by nature, by the geography, so even when he speaks of how he envisioned Absolute World, it's something that's spiralling up from the ground. He ties it to nature and the ground - a root, a tree trunk - those are the things that he uses to describe them, and that's how he designs. He's doing some stuff in China, and some of them are in desert conditions and he gets inspired by the dunes and that kind of influence.

From a business point of view, was it difficult putting all of your trust in a young architect?

I thought this guy was crazy [laughs]. I would scratch my head wondering 'what have we done', but we saw it from the very beginning. It's not like you hire someone and you don't know what they're going to produce. The good thing about what we did with the competition was that before we hired the guy, you saw the result of his labour. We knew that even if he didn't have the ability to produce the working drawings which we needed to build the thing, we had that talent available to us locally. All we needed from him was aesthetic input, but from day one I was concerned that our guys here were gonna take it and completely change it, so I defended that design and Yansong all the way through the process. I wanted to make sure that it was authentic, and that he stayed involved in the process, and that nothing got changed without his blessing. What happened as a result of the process, most of the changes were actually done by him. It wasn't our guys [Burka Architects]. Our guys maintained the authenticity of the original design, but he was the one that kept tweaking and refining it. We gave him a great deal of latitude.

On the constructibility side, I understand that Dominus had to innovate with the construction process, for example adding thermal breaks under the balconies. Tell us about about how this build differed from conventional builds, and what other innovations you had to develop for Absolute World.

Typically your hoist sits outside the building, but because of the cantilever, the distance between the hoist and some of the floor plates was too great. We took the hoist and put it inside the elevator core, which isn't a good thing because it ties up that space. It wreaks havoc on the scheduling, so you have to understand this and build it into your schedule and your budget. Because of that cantilever we had thermal bridging issues, so we had to figure out a way of dealing with that.

View of thermal break installation underneath each floor plate. Image by Jasonzed.

View of thermal break installation underneath each floor plate. Image by Jasonzed.

View of thermal break installation underneath each floor plate. Image by Jasonzed.

View of thermal break installation underneath each floor plate. Image by Jasonzed.

Had that ever been done before?

To some degree it had, but we took some methodology that was tried, tested, and true, and adapted it. We didn't reinvent the wheel. We just took the wheel and made it a little better: the application was slightly different. The basic cladding system was probably the easiest, it's a window wall system - slab to slab - so the only difficulty there was making sure that the window walls are where they have to be. We spent considerably more on surveying costs, just making sure that the structure is where it needs to be, the window wall system is where it needs to be, the slab edge is where it needs to be, more so than you would on a conventional building.

Did you bring in any other experts for this project that you wouldn't normally have brought in for another project?

No, we didn't have to bring in any other discipline than what we normally would use. We've got some great people in the city of Toronto, people who do work all over the world. We're looking for inspiration elsewhere in terms of design, but when it comes to actually executing the working drawings or construction, we've got some of the best talent here in Toronto.

Moving on to L Tower. How did you come to bring Daniel Libeskind in for this project, known for his deconstructivist approach to architecture?

We partnered up with Castlepoint, and we actually came in late in the game, so Libeskind was already engaged in the project when we got involved. I think a lot of that came from the City. Alfredo Romano (of Castlepoint) also believes in great design and hiring the best architects, so we share that in common, but the City wanted - because of their involvement with the Sony Centre - to elevate the architecture, so they influenced that decision. When we showed up he was already on the scene, but one of the reasons we got involved was because they had Libeskind. It helped us decide that we wanted to get involved.

Render of L Tower. Image courtesy of Cityzen.

Render of L Tower. Image courtesy of Cityzen.

Was that your first partnering with Alfredo Romano then?

Yes, that was the first project with Castlepoint. The second was Backstage, which is the second phase of L Tower, even though it's separated by a roadway.

Had you acquired that land when you partnered with Castlepoint?

At the time those discussions had started with GO, but as you recall at the beginning, the only interest we had in that land was accommodating parking for L Tower. What we were supposed to build there was an office building for GO Transit. Then they were given some directive that they had to locate within the Union Station redevelopment, so it freed up that land, and they [the City] came to us and said, 'Is there anything you guys can do with this?' We didn't want to build an office building on spec, so we said that the only thing we could probably do with it is build another residential tower. They gave us that approval and we moved forward with Backstage.

ArtsLab was to make up the lower floors of L Tower. It was unfortunate that it had to be scrapped, both from an architectural and a cultural point of view. Can you tell us more about that component of the project, and what kept it from getting off the ground?

ArtsLab was never something that we were involved in, it was the City. Conceptually it made a lot of sense to have a venue such as that attached to the Sony Centre. The City was prepared to invest some money, but they needed more from the Province and the Feds, and neither stepped up to the plate, and we had to move forward with the project. At some point they came to us and said 'there's this 100,000 sq ft of space, can you guys do something with it other than residential?' So we called in Barry Sternlicht from Starwood Capital and we explored the possibility of putting a hotel into that space, a boutique which we thought was a great idea, but the timing was off and the markets at that point were collapsing. If it had been earlier or even later, we probably would have cut a deal with one of the boutiques. The other thought was, if not a hotel, what about retail? Again, we got caught mid-market in terms of the real estate industry and where we were headed. Even though the signs were still positive, the Canadian retailers weren't interested in moving forward. We approached some of the US retailers who had expressed interest, but when things started to worsen they all pulled back, which is a shame because if it were today, what's leading that retail pack in Canada is all those US retailers. All of a sudden Nordstrom, Coles, Marshalls all want to be here. We're right in the middle of that with 3C [a joint venture on the waterfront site between Cityzen, Castlepoint, and Continental Ventures of New York], because 3C is going to have a major retail component to it. We probably could have done something here, just the timing was not right.

Had the City put a cap on the amount of residential space there and that's why you weren't just able to turn the boot into residential?

They wanted to retain ownership of that land, so you either build a rental apartment building, which we didn't want to do, or have to find another use for it. So the City ended up loosing that 100,000 sq ft. It actually ended up being a very positive thing for L Tower because some of that lower space in L Tower was repatriated. We added more units to the actual tower itself, and created the loft units. We also had all our amenities buried on level 3 or 4, so we were able to take all those amenities and bring them up and created that little, call it the lean-to, the pavilion, so that made for a much nicer amenity venue. It was all very positive for the L Tower, but obviously not the best situation for the Sony Centre. We're going to get a very nice plaza. Claude Cormier is working on the landscaping, so the Sony Centre can do something with that outdoor plaza. It could be a place where you have outdoor theatre. It will be an interesting place right at the corner of Yonge and Front.

Since around the time that the L Tower weather wall went up it's been rather slow to rise [as of interview in mid-August]. Can you update us on what's currently taking place, and how we'll expect to see the project proceed in the upcoming months?

In these lower floors is where the structure does weird things. It's time consuming in the forming. They set up the RCS forming system. We're on level 8 now, so from here on in, I think we're looking at a four day cycle - I'm looking at a four day cycle [laughs] - so hopefully they can deliver within 4 to 5 days. It won't get better than four days. It's complicated.

Join us next week for part two as we continue our conversation with Sam Crignano about L Tower, the Cherry Street waterfront site, as well as Pier 27, 154 Front Street, and a candid conversation about the future.

4.6K

4.6K