There is no proposal, and there is no application, yet the planned Galleria Mall redevelopment is in some ways already more evolved than many of the submissions that come before the City of Toronto. Although a formal application is not expected until September, Freed and ELAD's planned redevelopment of the ageing Dupont Street mall is informed by months of community consultation and engagement.

Following extensive and ongoing community consultations, the pre-application was seen by the City's Design Review Panel on Tuesday, July 5th. Given the redevelopment's early stage, the voluntary review offered an additional guideline for the project's evolution, rather than a definitive assessment of the plan's strengths and weaknesses. As outlined in May, a dense, mixed-use community hub is envisioned, at minimum maintaining the 225,000 ft² of existing on-site retail space. Tuesday's review offered an updated—and more thorough—look at the plan so far.

The revamped park, including the new community centre (centre), image by Cicada Design

The revamped park, including the new community centre (centre), image by Cicada Design

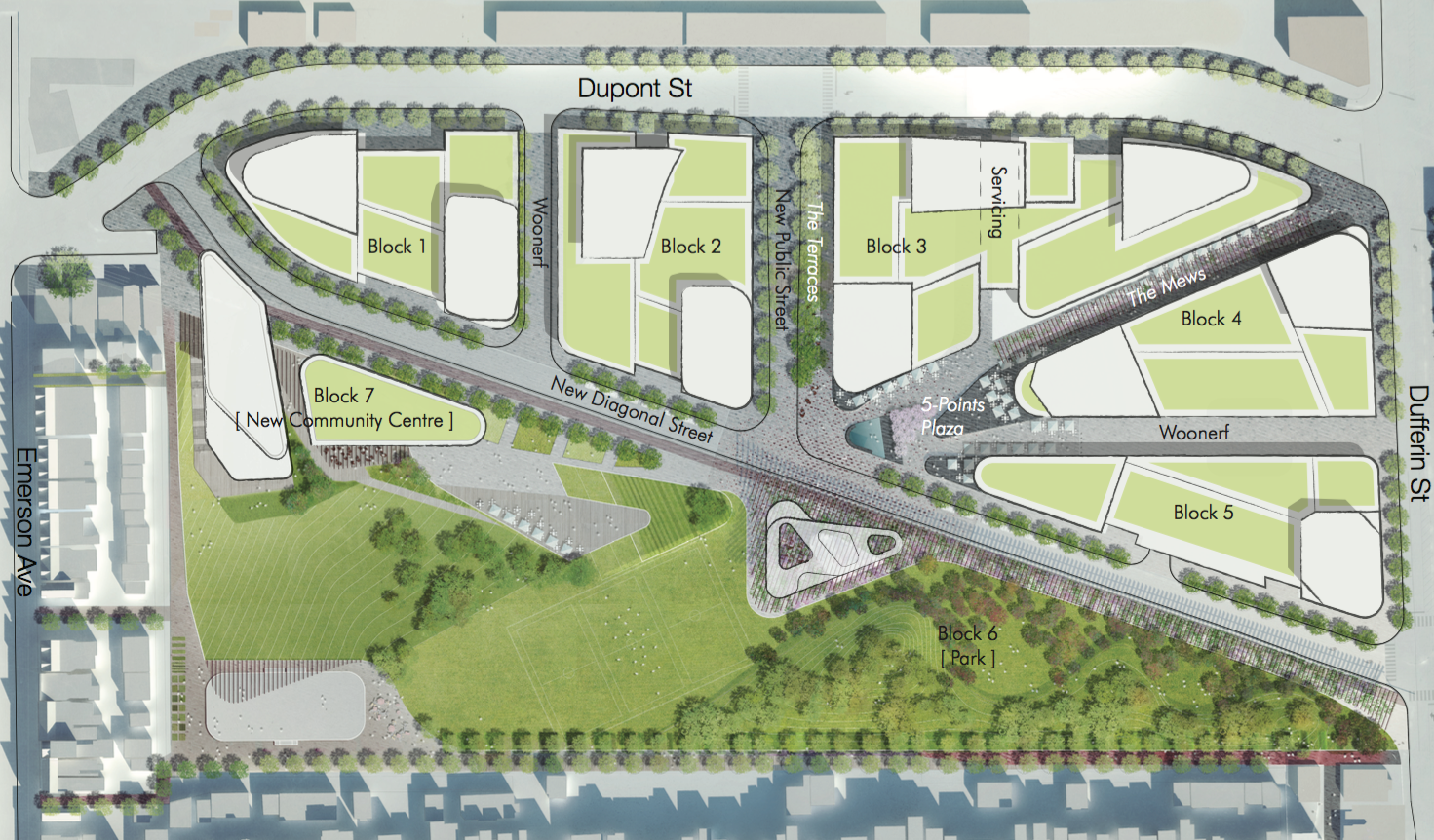

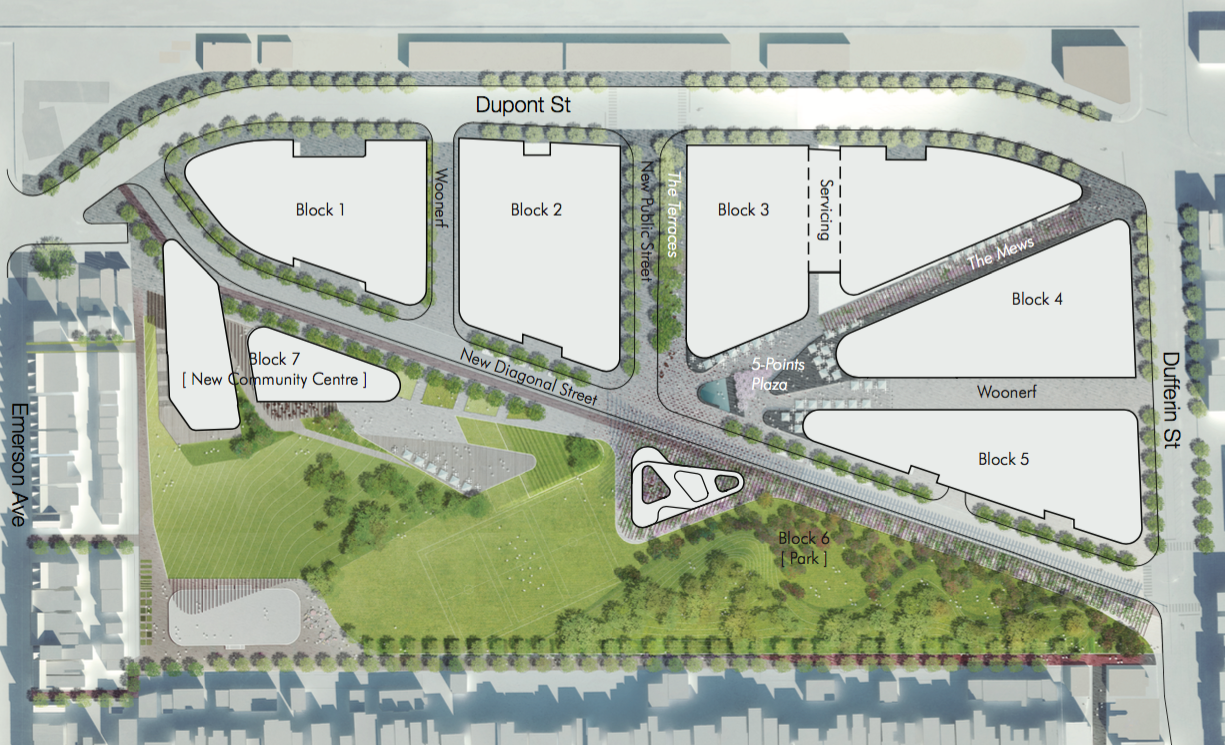

Depicting woonerf-style streets cutting through a diversity of architectural typologies above, the plan introduces new thoroughfares and towers, along with a revamped Wallace Emerson Park to the south. In addition, a new home for the Wallace-Emerson Community Centre is also envisioned, replacing the existing structure fronting Dufferin Street with a building—potentially featuring an active green roof—at the west end of the park (above). Alongside four new cross streets, which include a woonerf and a pedestrian mews, a diagonal thoroughfare would span the length of the block, connecting Dupont and Dufferin streets just north of the park.

The preliminary site plan, image retrieved via submission to the City of Toronto

The preliminary site plan, image retrieved via submission to the City of Toronto

It's important to keep in mind, however, that the renderings seen here are highly preliminary, and the design will evolve throughout the planning process. Nonetheless, the buildings depicted—which are part of a master plan by Hariri Pontarini Architects and Urban Strategies Inc—indicate the land use, massing, and the notional architectural expression that is being considered. Alongside the these plans, the project includes a landscaping plan by Public Work, as well as an emerging transit and mobility strategy by the BA Group.

A pedestrian-oriented woonerf is planned, image retrieved via submission to the City of Toronto

A pedestrian-oriented woonerf is planned, image retrieved via submission to the City of Toronto

Following an overview of the planning context by City staff, the development's guiding principles were outlined in a presentation by George Dark of the project's planning consultants, Urban Strategies. As explained by Dark, the site served industrial purposes prior to the opening of the Galleria Mall in 1972. Long before the mall's construction, the adjoining stretch of Dupont Street was curved to the north, accomodating an enlarged industrial site. The preliminary master plan retains the street's two curves.

Like the City representatives before him, Dark characterized the existing mall space as an outdated and inefficient retail space in the current context. However, he also acknowledged the Galleria's success as a community hub, stating that the mall is "arguably more successful as a community space" than as a retail destination. Indeed, despite the much-maligned mall's 'ugliness' and woefully outdated design, the space thrives as a gathering point for the surrounding Portuguese and Italian communities.

The Galleria Mall in 2015, image by Nicolas Arnaud-Godet

The Galleria Mall in 2015, image by Nicolas Arnaud-Godet

The six new blocks proposed all feature a retail-dominated street level, with a combination of commercial office and residential space above. At the east end of the reconfigured park, a new mixed-use block replaces the community centre at 'Block 5.' Meanwhile, the new community centre—which will include more diverse programming—is situated at the northwest of the park. In total, the reconfigured lot will see total park space increased increased by approximately 0.8 hectares.

A clearer view of the 7 blocks (with the park as Block 6), image retrieved via submission to the City of Toronto

A clearer view of the 7 blocks (with the park as Block 6), image retrieved via submission to the City of Toronto

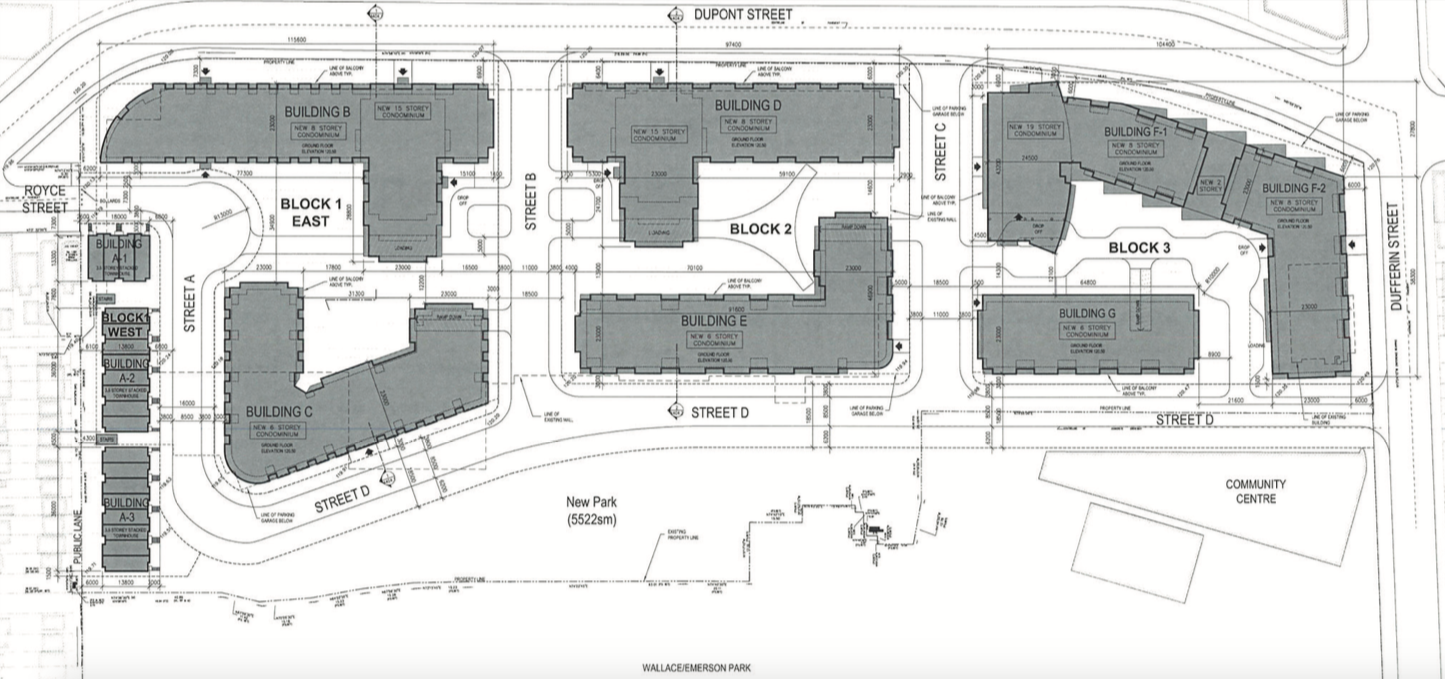

Although the current redevelopment plan introduces a radically changed neighbourhood, a similarly ambitious rezoning plan was approved by the City in 2004. Featuring six towers—with heights of up to 19 storeys alongside rows of stacked townhouses—the previous proposal (seen below) called for a total of 1,600 units, and some 1,500 parking spots. 38,750 ft² of retail space was planned, with the replacement of the mall reducing on-site retail by 85%. Four new streets were also planned, while major changes to the park and community centre were not part of the 2004 proposal.

The 2004 proposal (which left the park untouched), image retrieved via submission to the City of Toronto

The 2004 proposal (which left the park untouched), image retrieved via submission to the City of Toronto

With that proposal having accumulated dust for a decade, Freed and ELAD purchased the site for $80 million in 2015. Now, analyzing the two projects side by side over a decade later offers a telling comparison. A commitment to fine-grain retail, pedestrian-friendly streets, and a complete community, is underscored by the urban design. The frontages are now retail-lined, the streets are pedestrian-oriented, with new public spaces—including the '5 Points' plaza seen above—joining an improved Wallace Emerson Park and a new community centre. Above, each of the blocks will also feature a mix of residential and office space, all housed in what promise to be more architecturally ambitious edifices.

The 5 Points plaza, image by Cicada Design, courtesy of Galleria Developments

The 5 Points plaza, image by Cicada Design, courtesy of Galleria Developments

In terms of density, the proponents were not yet able to provide exact figures for building heights and total units. The development team conceded that somewhat greater density will be necessary in order to realize the project's ambitions, with a more concrete outline of height and unit mix expected in the Fall. The new plan will also likely include only 500-600 parking spaces, reflecting a much less car-oriented community. While the BA Group's transit and mobility strategy is still being developed, the proponents hope to bring on-site transit to the new diagonal street connecting Dufferin and Dupont. Dark also noted that the emerging mobility hub between Dundas West and Lansdowne along Bloor—served by GO, TTC, and UPX—is a 15 minute walk away from the site.

The developers hope to introduce on-site TTC transit, image retrieved via submission to the City of Toronto

The developers hope to introduce on-site TTC transit, image retrieved via submission to the City of Toronto

Given the plan's preliminary nature—and its rather measured evolution—the height and density of the five new blocks has not yet been finalized. Notably, however, all five blocks are almost entirely blanketed by street-level retail, with a diverse collection of unit sizes planned. By introducing smaller retail spaces, the developers hope to foster a fine-grained environment that's approachable to smaller, locally-owned businesses, with the diversity of spaces ideally reflected by a similar diversity of retailers.

The street-level uses, with retail in light orange, click to enlarge, image retrieved via submission to the City of Toronto

The street-level uses, with retail in light orange, click to enlarge, image retrieved via submission to the City of Toronto

Ahead of the concurrent Official Plan Amendment and Zoning By-Law application submissions planned for September, vital elements of the plan are still underway. In the coming months, the sustainability, built form, and mobility strategies are expected to take shape, along with a more detailed breakdown of land uses, and a phasing plan that will inform the project's gradual build-out. An affordable housing strategy for the site is also taking shape, alongside the aforementioned mobility and transportation plan.

An evening view of the pedestrian mews, image by Cicada Design, courtesy of Galleria Developments

An evening view of the pedestrian mews, image by Cicada Design, courtesy of Galleria Developments

Ahead of the DRP's comments, the proponents stressed that the plans seen so far, and the proposal to come, are rooted in community input. A series of open houses—and more focused working groups—was held long before the application is to be submitted, with the DRP review similarly preceding the typical process. Indeed, the preponderance of retail space, the pedestrian-oriented street level, and the mixed-use towers above, all reflect community priorities. Similarly, the integration of the park and community centre into the scope of the redevelopment also emerged through the consultations.

***

Following the presentation, the DRP members provided some preliminary commentary and guidance. Universally, the panelists were happy to see the proponents "come in for a pre-application meeting." Panel members praised the degree of respect shown to the community and the planning process, evidenced by both the pre-application open houses and the DRP review. Given the plan's evolving status, the comments were not as specifically focused as the feedback typically given to submitted applications.

Nonetheless, panelists identified a number of elements that may require further attention from the design team. While the diagonal street was celebrated as "an opportunity to create a new character" by deviating from Toronto's street grid, the northwest terminus was seen as somewhat unresolved, with uncertainty as to how the street will integrate with Dupont. Meanwhile, the boundary between the park and the private properties to the south was referred to as "undefined," warranting more consideration.

A closer view of the community centre, image retrieved via submission to the City of Toronto

A closer view of the community centre, image retrieved via submission to the City of Toronto

Although the degree and diversity of retail was praised, the panelists questioned whether street-level vitality can be maintained throughout the site, worrying that the retail spaces along Dupont may not be as successful as those lining the internal streets. One panel member called for a more careful plan for "the nature of the ground level on Dupont," while another also identified a need to "amplify the identity of the park along Dufferin," arguing that the current green space is too isolated from the surrounding city. The positioning of the community centre and the ice rink were also a cause for concern, with some panelists worrying that both facilities—which also "lack reference to one another"—are too far from the centre of the community.

Overall, however, the plan was enthusiastically received. The commitment to a vibrant public realm and a complete community was a particular highlight for panelists. On this topic, one panel member argued that "the success of this will be how you treat the street," adding that high-quality paving material—"not asphalt"—are needed to create successful public spaces and pedestrian areas.

"The real test is how do you take this and make it feel like it's an extension of the neighbourhood, and that the design you come up with couldn't be anywhere else," a panelist told the proponents, crystallizing the earlier commentary. Following the comments, the last note was one of high praise. "If this could be done, it could become a benchmark for the city."

***

What emerged from the review and the presentation is a very promising plan. Although critical details—including affordability and mobility—are yet to be fully worked out, a commitment to fostering a functional and complete community is readily apparent. For a site in obvious need of redevelopment, ELAD and Freed are moving in a positive direction, showing sensitivity to the local context while promoting a vibrant and walkable urban space.

Yet, for all of the project's obvious strengths, losing the Galleria Mall—maligned as it is—could also mean losing a gathering space that's vital to the neighbourhoods around it. Despite (or perhaps in spite) of its obvious lack of appeal, the Galleria Mall is a lively hub for the area's immigrant communities, the same immigrant communities that often become marginalized in more 'attractive' urban spaces.

Characterized as a sort of "Portuguese-Canadian version of Cheers" by Shawn Micaleff, the Galleria Mall in some ways retains the atmosphere of a village, where some are even greeted by name as they enter. Similarly, The Toronto Star's Edward Keenan nostalgically celebrated the mall's uniquely neighbourly ambiance. Earlier this year, Keenan invoked Jane Jacobs in suggesting that "ugly" buildings like the Galleria Mall can serve an important social purpose.

Looking west across the parking lot, image by Nicolas Arnaud-Godet

Looking west across the parking lot, image by Nicolas Arnaud-Godet

Like the disused factories and derelict Victorian houses defended by Jacobs in the 20th century, more recently built strip malls and warehouses are this era's refuges of affordability. While the red bricks and cornices of the late 19th century are now imbued with cachet and social prestige—often fitting into the same developer agendas that Jacobs once sought to protect them from—places like the Galleria Mall can be surprising incubators of vitality. "You can wander around in the older parts of the city, the gentrified or gentrifying ones, and notice that it is the tinier and uglier storefronts that tend to house the remaining outposts of eccentricity," Keenan writes.

None of this is to say that the site shouldn't be redeveloped. On the contrary, it's hard to argue against the fact that the Galleria Mall is an extremely poor use of urban space, that's it outdated and inefficient. It's also hard to argue against the myriad benefits of the new development—if it proceeds as envisioned—which, despite some concerns, have proved reasonably popular with the surrounding communities. As Keenan notes, "'[s]ave the eyesores'... seems like a misguided kind of rallying cry" anyway. On balance, Freed and ELAD's development will likely be a major improvement for the site. In many obvious ways, the thoughtful, contextually sensitive development promised won't be nearly as bad as the Galleria Mall. In another way, it might never be quite as good. For a project that seems to be worth celebrating, it's worth acknowledging that too.

***

Want to share your thoughts about the upcoming proposal? Feel free to leave a comment in the space below this page, or join in the ongoing conversation in our Forum thread.

3.3K

3.3K