kali

Active Member

^yeah idk about that. I would much rather separate, protected cycle lanes.

If you aren't a traffic engineer or an urban planner, the word woonerf probably looks like a typo, or maybe the Twitter handle of whoever runs marketing for Nerf (woo!). But you might want to get familiar with the term—Dutch for "living street"—because the urban design concepts it embraces are on the rise.

A woonerf is a street or square where cars, pedestrians, cyclists, and other local residents travel together without traditional safety infrastructure to guide them. Also sometimes called a "shared street," a woonerf is generally free of traffic lights, stop signs, curbs, painted lines, and the like. The basic idea is that once these controls are stripped away, everyone is forced to become more alert and ultimately more cooperative. Through less restraint comes greater focus.

The decades-old vision is not without its critics. Skeptics wonder if drivers feel too much ownership of the road to adapt their ways, or if shared streets can work fine for smaller towns but not in big urban centers, or if removing oversight is naïve at a time when people won't even stop texting to drive. Then there's the general critique pointed out by Traffic author Tom Vanderbilt in a 2008 article about shared streets: "people do act like idiots."

All fair points (especially the last). But woonerf supporters can point to the success of shared streets projects in Europe as well as their gradual adoption in other parts of the world—including major cities in the auto-centric United States. Construction of Chicago's first shared street, for instance, is expected to begin this spring.

We took a closer look at six places around the world that have woonerfed and emerged better for it.

I sent this VERY interesting link to my Councillor (Kristyn Wong-Tam and she sent it to Transportation. THEY just responded:Interesting Study here on hardening the centre-line at left turn locations to improve safety.

It appears to show a very significant improvement.

Simple infrastructure changes make left turns safer for pedestrians

Centerline hardening can dramatically reduce close calls between vehicles and pedestrians.www.iihs.org

Before

View attachment 261392

After

View attachment 261393

A picture is also included in the link; but does not appear to me to fully match the diagram.

View attachment 261394

Background

Pedestrian related deaths have recently been on the rise in Canada. The effect of changing posted speeds on the frequency and severity of pedestrian motor vehicle collisions (PMVC) is not well studied using controlled quasi-experimental designs. The objective of this study was to examine the effect of lowering speed limits from 40 km/h to 30 km/h on PMVC on local roads in Toronto, Canada.

Methods

A 30 km/h speed limit on local roads in Toronto was implemented between January 2015 and December 2016. Streets that remained at a 40 km/h speed limit throughout the study period were selected as comparators. A quasi-experimental, pre-post study with a comparator group was used to evaluate the effect of the intervention on PMVC rates before and after the speed limit change using repeated measures Poisson regression. PMVC data were obtained from police reports for a minimum of two years pre- and post-intervention (2013 to 2018).

Results

Speed limit reductions from 40 km/h to 30 km/h were associated with a 28% decrease in the PMVC incidence rate in the City of Toronto (IRR = 0.72, 95% CI: 0.58–0.89). A non-significant 7% decrease in PMVC incidence rates were observed on comparator streets that remained at 40 km/h speed limits (IRR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.70–1.25). Speed limit reduction also influenced injury severity, with a significant 67% decrease in major and fatal injuries in the post intervention period on streets with speed limit reductions (IRR = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.13–0.85) compared with a 31% not statistically significant decrease in major and fatal injuries on comparator streets (IRR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.37–1.31). The interaction term for group and pre-post comparisons was not statistically significant (p = 0.14) indicating that there was no evidence to suggest a pre-post difference in IRRs between the intervention and comparator streets.

Conclusions

Declines in the rate of PMVC were observed on roads with posted speed limit reductions from 40 km/h to 30 km/h, although this effect was not statistically greater than reductions on comparator streets.

Background

In 2015, pedestrians accounted for 15% of all road traffic-related deaths in Canada. In addition, a 2011 OECD report noted that Canada was one of only seven industrialized nations where pedestrian-related deaths had increased over time. In the City of Toronto, over the 12-year period 2005 to 2016, inclusive, 2172 pedestrians were killed or seriously injured after being struck by a motor vehicle.

Lower speed roads are associated with a reduced risk of pedestrian motor vehicle collision (PMVC) as well as less severe PMVC injuries. A comprehensive literature review that examined pedestrian fatality risk as a function of car impact speed showed that for every 1.6 km/h reduction in speed, PMVC frequency was reduced by 5%. The chance of surviving a collision with a motor vehicle traveling at 50 km/h is less than 20%; whereas, survival increases to 50% at 40–45 km/h and 90% at 30 km/h. Globally, studies in South Africa, New Zealand, Europe, and North America have shown that average vehicle speeds are reduced by 8–40% after speed limits are lowered from 60 km/h to 50 km/h. A meta-analysis of impact speed and pedestrian fatality risk supports setting speed limits of 30–40 km/h for high pedestrian activity areas as the risk of a fatality reaches 5% at an estimated impact speed of 30 km/h [8]. Although many studies report a reduction in severe PMVC injuries and crash risk after lowering speed limits, speed limit reductions have not been well studied using controlled quasi experimental designs.

Reasons for the increased likelihood of a crash at higher speeds include a reduced field of vision, shorter reaction time, and increased stopping distance once the brakes are engaged. At lower speeds, pedestrians can make more effective decisions about when to cross the road and drivers have sufficient time to stop. Toronto’s Vision Zero Road Safety Plan has proposed posted speed limit reductions from 40 km/h to 30 km/h on local roadways in an effort to reduce severe and fatal PMVC injuries. However, there are few pre-post studies that examine the effect of such speed limit reductions on PMVC. The aim of this study was to examine the effect of reducing posted speed limits from 40 km/h to 30 km/h on incident rates of PMVC in Toronto, Canada.

Intervention

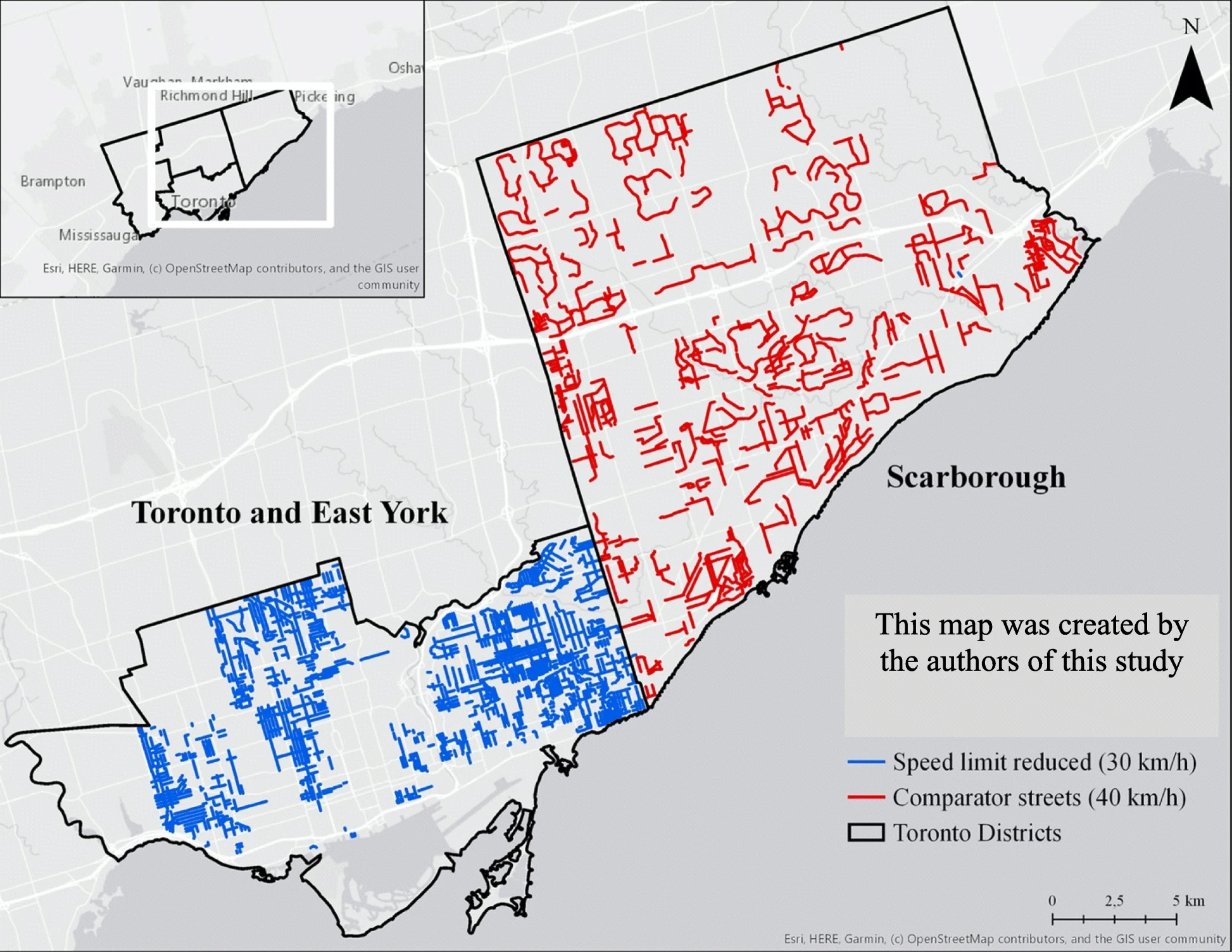

Between January 2015 and December 2016, the City of Toronto used a blanket approach and reduced the posted speed limit from 40 km/h to 30 km/h on all local roads within 12 Municipal Wards in the Toronto and East York District (see Fig. 1). The location of streets with speed limit reductions and the dates of implementation of the intervention were obtained from the City of Toronto, Transportation Services Division. Street names were used to identify street segments within a map of the Toronto road network, to determine the number and length of street segments that had posted speed limit reductions.

The critical part of woonerf is designing the street in a way that people don't speed, overtake, etc. in dangerous ways. That means bumpy surfaces, chicanes, narrow lanes, etc. It's not enough to have a low speed limit--the street design has to support that speed limit being the max comfortable speed.Since e-bikes and e-scooters are not supposed to exceed 32 km/h, any roads with speed limits of 30 km/h therefore (ipso facto) shouldn't really need their own lane. Ditto with motor vehicles, bicycles, tricycles, skateboards, etc.. Streets with a speed limit of 30 km/h (or less) are "shared streets".

6 Places Where Cars, Bikes, and Pedestrians All Share the Road As Equals

The woonerf, or "shared street," has made its way

See link.

The critical part of woonerf is designing the street in a way that people don't speed, overtake, etc. in dangerous ways. That means bumpy surfaces, chicanes, narrow lanes, etc. It's not enough to have a low speed limit--the street design has to support that speed limit being the max comfortable speed.

This. Which is why I think it's silly lowering speed limits on the massive arterials without changing the actual roadway design.

Part of the problem is that woonerf are effectively illegal in Toronto due to emergency vehicle access requirements. Maybe that needs to be rethought, including changing the fleet of emergency vehicles to support narrower streets in built up areas. It's obviously possible to have that street design and still ensure access for emergency vehicles--we're not inventing anything new.

^I’m not sure that the bigger emergency vehicles are the ones that are a problem. It’s the springs in the typical well-worn police cruiser that won’t handle a speed bump. Ambulances could be a concern, but smaller lighter ones won’t take a speed bump thatbwell either.

A better approach might be to set a limit on how many such impediments there can be on the first-due path between fire/ems stations and the furthest destinations.... or within say 1 km of hospitals with emergency wards.

Firefighters and paramedics are damn good at wheeling thise big rugs thru tight spaces (there are limits, sure).

I’m inclined to think that with a bit of analysis and data collection, and judicious application, one might be able to accomplish a lot, where the police and fire chiefs just routinely naysay each and every proposal.

- Paul

The issue, to my mind, its not a wholesale ditching of larger vehicles; but it is having the option of smaller ones to permit more efficient land use and creative forms.