on further investigation, it does appear that the work did in fact receive an appropriate level of attention, 20 years ago or so, including a large retrospective curated by the then "National Archives"

so it is more in the nature of a revival of interest that is necessary.

this is from Lexis Nexis, so i can't link to it. full text follows:

THE VISUAL ARTS A glassful of life, art and cold beer

Globe and Mail, Saturday, November 21, 1992

MICHAEL TOROSIAN

Toronto ONT -- Michel Lambeth is one of the most important figures in the history of Canadian photography and the subject of one of the most extensive retrospective exhibitions ever mounted in Canada. Produced by the National Archives, Michel Lambeth: Photographer concludes its six-year national tour at The Market Gallery in Toronto, from Nov. 28 to Jan. 24. The exhibition was curated by photographer and publisher Michael Torosian, a student and close friend of Lambeth, who 15 years after the artist's death offers this remembrance.

BY MICHAEL TOROSIAN Special to The Globe and Mail Toronto

THIS past September marked 20 years since I first met Michel Lambeth. In 1972 I was entering my final year in the photographic arts program at Ryerson Polytechnical Institute in Toronto, where Michel was teaching a studio critique class. Our first encounter was a private interview. We talked comfortably as he smoked, consumed cough drops and displayed the slight symptoms of a cold that would never seem to fully leave him. I would never have guessed that day how largely Michel Lambeth would figure in my life.

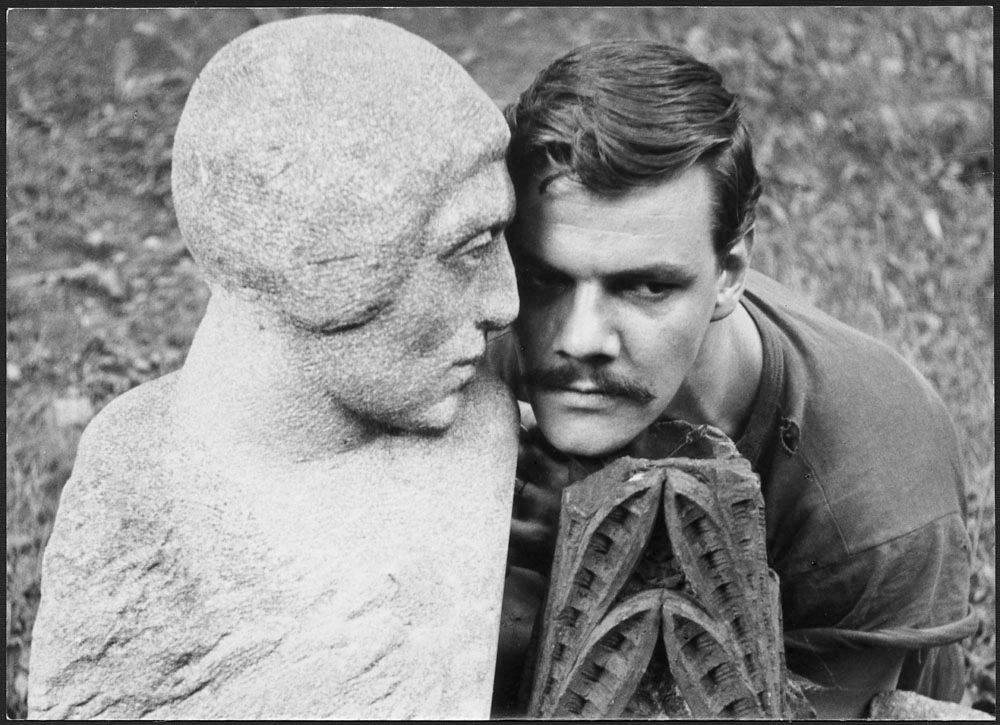

By the time I met him, Michel was, at the age of 49, a significant figure in the world of Canadian photography. He had had a distinguished career as a photojournalist and writer, but I knew his work best through the exhibitions and publications of the National Film Board. Michel's work commanded attention; it spoke to me. His photographs possessed an artistically subtle polish and were infused with a vision that faced reality without flinching and seemed always touched with a whimsical sense of humour. I was excited at the prospect of having him as a teacher.

Our workshop was an informal, improvisational environment, a laboratory of exploration in which Michel was relentlessly encouraging. However, for me the main event of the day began when the class ended. From the beginning Michel and I, along with my friend Rene, got into the habit of marching out of the school building at the stroke of 1, down the alleyway to Dundas Street, and into the Imperial Pub. This was the location of the coldest, most refreshing draft and our forum on life and the arts. Twice a week for the entire year we observed an afternoon-long ritual. We invariably sat at one of the little round tables bathed in the glow of an aquarium that was recessed in the wall and populated with neon fish. A TV, mounted high above us, was always on, the volume always off; a disused shuffleboard was tucked along one end of the room, the remnant of a more prosperous and ebullient era in the Imperial's history. This was where my education took place.

Michel was extraordinarily cultivated in the passionate manner of an autodidact. His formal education largely ended with his graduation from Toronto's Eastern High School of Commerce in 1940, but he was a voracious reader and apparently totally absorbed by the arts from a very early age. Postwar art studies in London and Paris fleshed out and consolidated his commitment. This period of his life was a fertile source of anecdotes, a time of art history classes at the Louvre, of studying sculpture at the studio of Ossip Zadkine and selling Communist newspapers in Place Contrescarpe. Among the stories, Michel offered this piece of advice: "My master Zadkine once told me, 'Do something every day. Whether it is preparing an armature, doing preparatory drawings or actually working on the sculpture. No matter how important or trivial the activity seems, don't let a day lapse.' " A golden rule for a tyro, and the most important guidance Michel ever gave me.

My favourite story was about a Parisian girl he'd fallen in love with after the war. As he told it, he went to the immigration office with the thought of permanently staying in France so he could marry her. When asked what his occupation was he replied, "Artist." The clerk on duty told him, "Now that the war is over, Paris is in need of carpenters and plumbers and bricklayers. We don't need artists, we have plenty of them." He was refused.

The pattern of our afternoons was a patchwork of analysis and celebration of art. Michel often referred to those photographers he admired, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Brassai, Robert Doisneau and Andre Kertesz. His own photographs embraced their language - the "decisive moment," the drama in visual structure, the irony in life - informed with a humanity and insight that gave Michel's work a signature all its own. His portrait of Toronto in the 1950s is unparalleled in its synthesis of autobiography and observation.

The days grew longer as the spring of 1973 approached, but you wouldn't have known it from within the Imperial. There was a fake window with frosted glass from behind which a couple of apathetic light bulbs manufactured perpetual dusk. We were in our own world, intoxicated by esthetics and beer.

Rene and I were shocked when Michel told us that his 50th birthday was approaching. We exclaimed that he looked no more than 35. In the Imperial he was a gregarious, robust, youthful man. There was no hint then of the depression that would intermittently mark his life over the next four years. But even in those years we had a lot of good times, our conversation just as lively, as we worked together on an exhibition of his photographs.

After Michel's death in 1977 I came into possession of his artistic estate and for the next nine years was the cataloguer and caretaker of his many thousands of negatives and prints and personal documents. Through the organization of two retrospective exhibitions and an array of publications, I sought to lay a foundation for future study into his life and work. I read everything that Michel had ever written, as well as everything about him. I interviewed his family, friends and colleagues.

As the years went by and my work on Michel deepened, I was no longer sure what knowledge I had from personal experience, and what I'd gleaned from another source. I felt at risk of losing my memories of him as a friend - he had now become the subject of an art historical pursuit: fascinating, but remote.

It's been more than six years since I worked on the Lambeth collection in an official capacity. One day not long ago I was looking at a little sculptural assemblage Michel had given me. It was old and the glue on some of the components had become desiccated. As I held it, a small panel came off in my hand, revealing a clipping from a newspaper. This was something that was never meant to be seen. It was a comical little squib about the battle of the sexes that was perfectly in stride with Michel's sense of humour. The miasma of confusion that had so long obscured my memories dissipated. I could see Michel again in the Imperial, drinking beer, smoking cigarettes and relating this story to the enormous delight of Rene and me. There we were, in a rundown pub with a regal name, an ethereal joint.