afransen

Senior Member

Having them too close takes away from the 'rapid' aspect.

3 hour periods = short bursts. got it.

View attachment 274823

You people have never ridden a fully automated system, have you?

They make the Yonge Line feel clunky and slow. And the number of systems built and under construction with the ability to run at 90 seconds from day one are numerous.

I wouldn't call 6 hours a day "short bursts"... Victoria line services to increase in major boost for commuters - New timetable means trains arrive every 100 seconds for around three hours during weekday morning and evening peaks

There are many lines in the world that run at least 30tph ... I can think of at least 4 lines in London alone!

High frequency, automated train operation is going to be revolutionary for Toronto - the City hasn't yet experienced the quality of service that can be delivered under ATO CBTC on Line 1 either!

Let's just focus on the immediate Ontario Line proposal on our hands. Any further northern extension from Don Mills is straying into fantasy land, and it wont happen in any of our lifetimes (including babies who are born today).

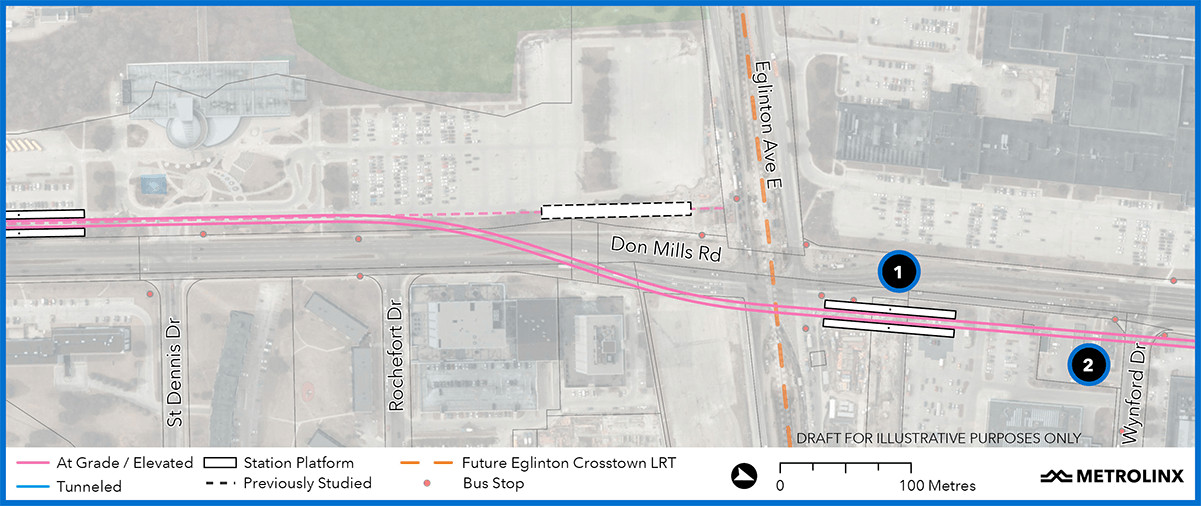

I think image "4" was added to the site today for the "Thorncliffe Park" tab.

The Ontario Line - Neighbourhood Updates - North

The following maps show the alignment, or route of the line, and the proposed location of station platforms. Station structures, entrance locations and initial design concepts will be shared as further design work is completed. Teams continue to study how to minimize community impacts and...www.metrolinxengage.com

View attachment 274894

Hey, you never know. A couple of years ago, Relief Line North was a 2035-2040 kind of thing and a subway going west from downtown was the fantasy land. And now we're here.

The line in your table is running at 100 second intervals. The Ontario Line is "planned" for 90 second intervals. That's an 11% drop in throughput and capacity (equivalent to about 3,300 riders per hour, on the Ontario Line). Every second matters for capacity.

This is going to sound very nitpicky, but the difficulty in operations increases almost exponentially the closer you get to the illustrious 90 second mark. This is a lesson we learned here in Toronto with our own implementation of ATO. Automatic signalling was initially touted as brining 90 second headways, however the TTC has since scaled back those expectations to about 105 seconds as more complexities emerged. The 15 second loss might not sound like a big deal to the casual listener, but that is a 16% loss in theoretical capacity, and several thousand fewer passengers that can fit on the line at peak hour.

These particularities do matter for the Ontario Line, especially given that the line hasn't been designed with a ton of extra capacity to handle additional extensions and natural increases ridership due to population growth and other factors. If achieved headways are, say, 10 percent less than planned, and ridership on the Northern extension is 20 percent higher than anticipated (and both of these figures are well within reasonable error bounds), the Ontario Line would be in a situation where it is overcapacity essentially upon the opening of any extensions.

Transit planning isn’t an exact science. Ridership and population growth is often dramatically overestimated or underestimated (indeed, Toronto's population growth has been significantly understated in planning documents). Different ridership models might very well produce ridership projections that are 50% off from one another. And capacity is fickle, especially as crowding increases. Many mass transit projects have been touted as supporting 90 second headways, but they typically fail to deliver those headways in actual operations. The Ontario Line would not be the first project to fail to live up to those expectations.

If the ridership and capacity estimates are spot on for the Ontario Line and any potential northern extension, everything will be fine. But if we’ve misestimated any of the variables involved, we could be putting ourself in between a rock and a hard place with regards to capacity. This is why it is important to design new rapid transit lines with a bit of extra capacity, in the form of properly sized trains,to have some breathing room if the numbers are a bit off. The only breathing room the Ontario Line has is provided by the purported 90 second headways, which are fickle and cannot be depended upon. We're essentially making a multibillion bet that these riderhip numbers and planned headways are spot on.

There's nothing special about 30 trains per hour. That's a third less trains than would be provided by 90 second headways. There's a world of difference between what we're discussing (40 tph, 90 seconds) and 30 tph (120 seconds)

It's been around for pretty much since day 1

AoD

The line in your table is running at 100 second intervals. The Ontario Line is "planned" for 90 second intervals. That's an 11% drop in throughput and capacity (equivalent to about 3,300 riders per hour, on the Ontario Line). Every second matters for capacity.

This is going to sound very nitpicky, but the difficulty in operations increases almost exponentially the closer you get to the illustrious 90 second mark. This is a lesson we learned here in Toronto with our own implementation of ATO. Automatic signalling was initially touted as brining 90 second headways, however the TTC has since scaled back those expectations to about 105 seconds as more complexities emerged. The 15 second loss might not sound like a big deal to the casual listener, but that is a 16% loss in theoretical capacity, and several thousand fewer passengers that can fit on the line at peak hour.

These particularities do matter for the Ontario Line, especially given that the line hasn't been designed with a ton of extra capacity to handle additional extensions and natural increases ridership due to population growth and other factors. If achieved headways are, say, 10 percent less than planned, and ridership on the Northern extension is 20 percent higher than anticipated (and both of these figures are well within reasonable error bounds), the Ontario Line would be in a situation where it is overcapacity essentially upon the opening of any extensions.

Transit planning isn’t an exact science. Ridership and population growth is often dramatically overestimated or underestimated (indeed, Toronto's population growth has been significantly understated in planning documents). Different ridership models might very well produce ridership projections that are 50% off from one another. And capacity is fickle, especially as crowding increases. Many mass transit projects have been touted as supporting 90 second headways, but they typically fail to deliver those headways in actual operations. The Ontario Line would not be the first project to fail to live up to those expectations.

If the ridership and capacity estimates are spot on for the Ontario Line and any potential northern extension, everything will be fine. But if we’ve misestimated any of the variables involved, we could be putting ourself in between a rock and a hard place with regards to capacity. This is why it is important to design new rapid transit lines with a bit of extra capacity, in the form of properly sized trains,to have some breathing room if the numbers are a bit off. The only breathing room the Ontario Line has is provided by the purported 90 second headways, which are fickle and cannot be depended upon. We're essentially making a multibillion bet that these riderhip numbers and planned headways are spot on.

There's nothing special about 30 trains per hour. That's a third less trains than would be provided by 90 second headways. There's a world of difference between what we're discussing (40 tph, 90 seconds) and 30 tph (120 seconds)

I agree with almost everything you said, but the Victoria Line is 50 years old. Planners have learned from that. The Skytrain can go as low as 70 seconds. Other lines routinely hold at 90 seconds during peak periods.

Line 1 will have its old infostructure weighting it down. The OL won't. So it is much more likely to hit the 90s target.

Except we're not here; in that there is no Relief Line/OL today.

Even seemingly minor details, such as poor pedestrian throughout at any individual station, can negatively impact your achievable headways (this is a huge problem at Bloor-Yonge).

How is it any different though if it was on the South Side? Now you have all of the passengers over at the northern end of the train? Not to mention, depending on how you construct the stations, it's quite easy to do a build where you dictate where passenger traffic will flow to. Let's say you have a station building on the North East Corner of the intersection. Since the line is elevated, you're going to need an Escalator to get to the platform. Depending on how high the platform is and where the escalator starts, it's entirely possible to have at least most pedestrians reaching the platform at around the midway.Heck, even looking at some of the early station layouts, we can already see some red flags in the design that might cause capacity issues on the Ontario Line in the future.

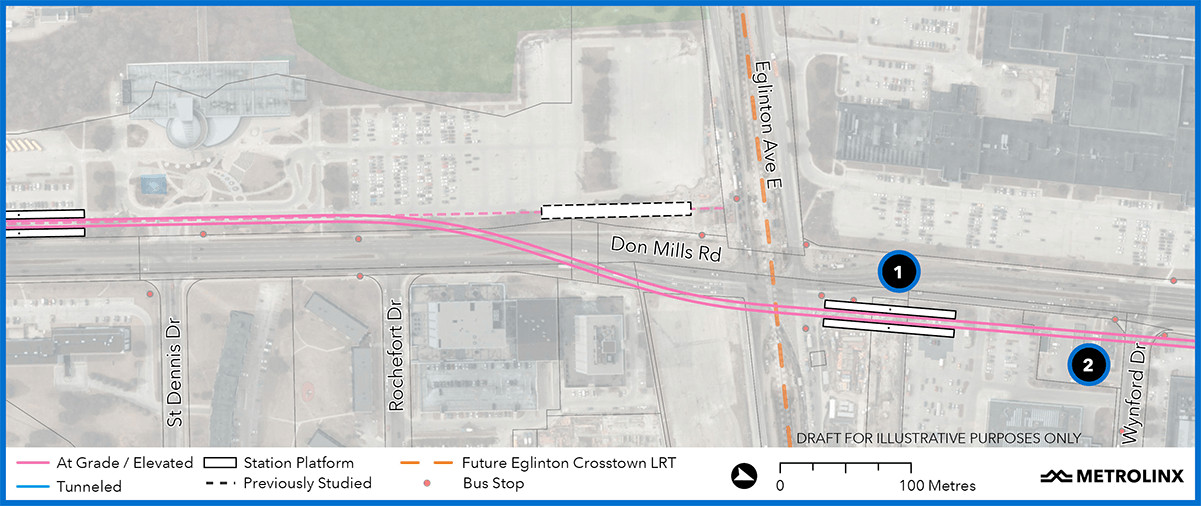

Notice that Eglinton-Don Mills Station (I refuse to call it Science Centre) on the Ontario Line is positioned entirely north of the Eglinton Line. Given this positioning, it's most probable that passengers who are transferring from the Eglinton Line to the Ontario Line will be entering the Ontario Line platform from the south side of the OL platform (this is the side closest to Eglinton Avenue). This is a big deal because it will result in poor load balancing on the OL trains. The south end of the train will be over capacity, while the north end of the train is empty. This means that passengers waiting on the south end of platforms at downstream stations (say, at Throncliffe Park or Pape Station), will be presented with totally full cars, and will be unable to board, despite the north end of the train largely being empty. At best, this will reduce the capacity of the line, as some passengers will not be able to board. At worst, this will reduce the capacity and the headways of the line, as badly behaved passengers hold doors in an attempt to squeeze into stations.

I know this sounds all very academic and nitpicky, but when you're trying to achieve 90s headways, you don't have the luxury of having any stations with poor pedestrian layouts, as this will impact your achievable capacity and headways.

We have a similar situation limiting the capacity of the Yonge Line right here in Toronto. Notice in the below diagram of the Bloor-Yonge station that the Line 2 platforms are at the north side of the Line 1 platforms. This results in passengers transferring from the Bloor Line, to the Yonge Line crowding at the north end of the Yonge Line platform, while the south end remains relatively empty. This causes a load imbalance on the trains, where the north of the train is overcapacity, while the south end is empty (you can see this effect if you watch Yonge Line trains pull into B-Y Station during rush hour). For the same reasons I described above, this culminates in a significant negative impact on the capacity and headways on the Yonge Line.

What this means is that even if the Yonge Line was could run at the 90s headways permissible by the TTC's ATO system, the poor layout of Bloor-Yonge Station alone would make running the trains at this frequency near impossible. And even if they could be run at that frequency, the poor load balancing on the trains would limit the effective capacity of the line, as the northern cars on the train will be over capacity, while the southern end is empty.

View attachment 274918

This highlights one of the reasons why I say 90 second headways, and their theoretically achievable capacities, are very fickle, and should not be depended upon. If those are the frequencies and crowding standards you're designing around, you have zero room to screw around with poorly designed stations and various other factors. It also means that value engineering (which the Ontario Line is susceptible to) could end up throwing away whatever theoretical capacity you thought you had.

For Eglinton-Don Mills Station specifically, Metrolinx needs to be very careful about how they're handling pedestrian distribution within the station. This is going to be one of the three most used stations of the line, so it is important that they encourage passengers to distribute themselves within the trains in the most efficient manner. Unfortunately the early design suggests that they're going to repeat the design mistakes of Bloor-Yonge Station.

But right now, "here" we are, discussing an exact route, looking at sketches for bridges & tunnel locations, and we have a proposed timeline for the next two-three years leading up to the start of work. People are arguing over station names and deliberating over precise little details like where a staircase might go. To me, that's a lot progress.