yrt+viva=1system

Senior Member

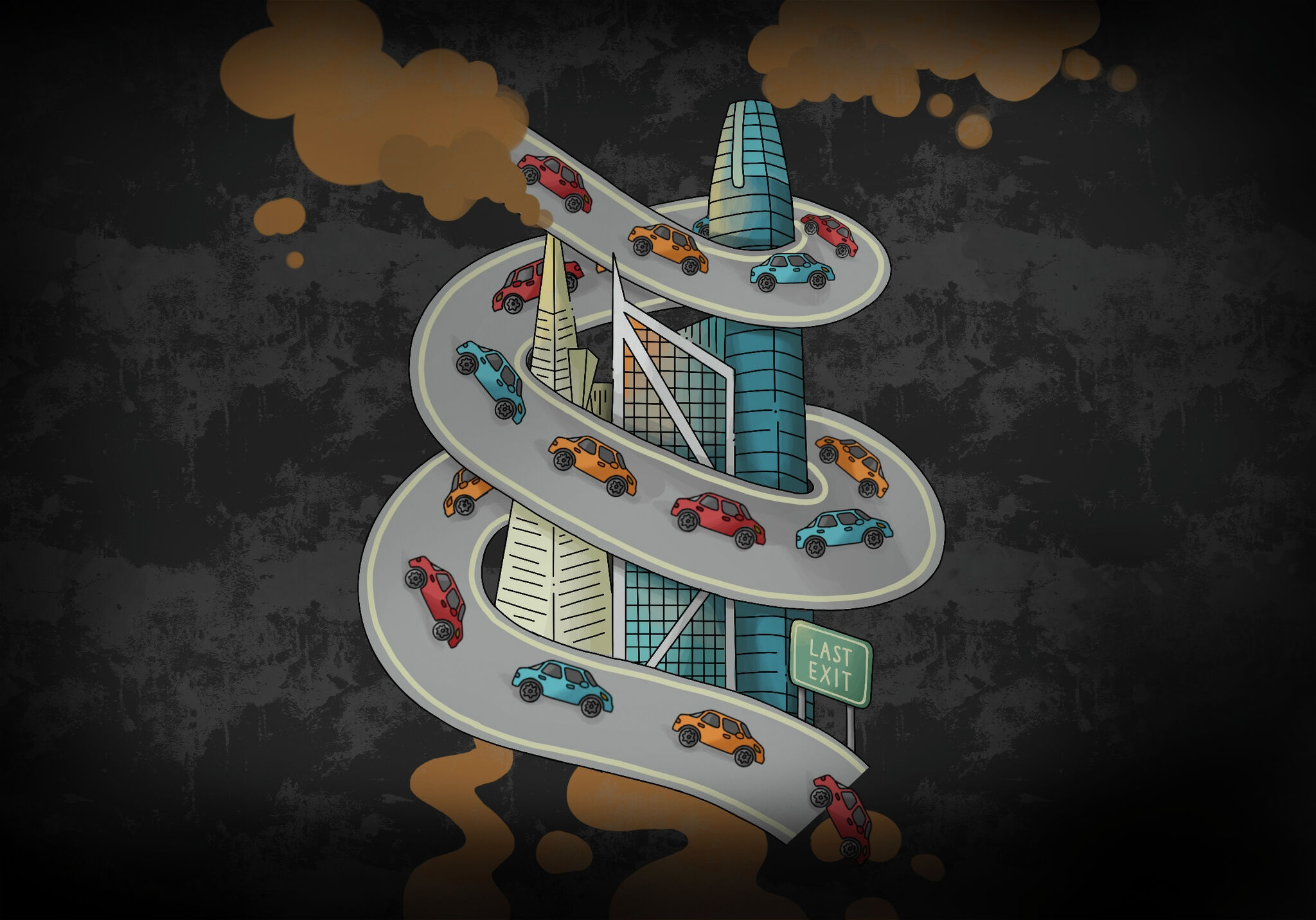

There wasn't an appropriate thread that covers the current situation of the vacant downtown core but this issue straddles both the urban life and politics realms. It's well documented that Toronto is a laggard when it comes to back to the office for work and this is starting to cause problems with the vitality of the core and the hollowing out process. There's ideas being thrown around from complete demolishment of office building to converting office buildings into much need residential space but so far no concrete plans and then there's the problem of politics and bureaucracy getting in the way of any sort of transformation.

This would be a good thread to discuss what the future of the downtown core may become. I'll start off with these two articles from The Globe and Mail and the Toronto Star:

https://www.thestar.com/business/20...ers-could-last-at-least-two-more-decades.html

This would be a good thread to discuss what the future of the downtown core may become. I'll start off with these two articles from The Globe and Mail and the Toronto Star:

In a hybrid work world, Toronto’s downtown core faces an existential crisis

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-toronto-downtown-businesses-hybrid-work/With a glut of office space and a shortage of housing, many cities are seizing on the prospect of conversion. In most cases these are easier said than done, made difficult by the scale and layout of many office buildings. Toronto’s downtown also remains particularly unfertile territory for this sort of work, with a city bylaw that legally protects office space in the financial district.

The city could not readily provide the number of recent conversions, but municipal staff said that very few had been completed since 2016, and most of those retained at least some office space. Only two applications for full conversion have been made since the pandemic began in 2020.

One of those projects is owned by H&R REIT. It wants to convert 69 Yonge St., the historic Canadian Pacific Building, entirely into residential. H&R argues that the structure’s age and design makes it unviable for today’s commercial office market, but the REIT wants to retain the exterior of the 15-storey heritage building, which was once the tallest in the British Empire.

“We want to find a way to give this building another 100 years of life, but for us to make that investment it cannot have any office,” said Matt Kingston, executive vice-president of development at H&R. “Even if it cost us nothing, there really is not much of a future in a building like this for office uses.”

He argues that the city’s conversion bylaw is outdated and too broad, not taking into account specific cases such as H&R’s project. But he declined to say what the firm’s next step might be if the city turns down its application.

Toronto chief planner Gregg Lintern acknowledged that the bylaw could prevent some repurposing, but the city is reluctant to move too quickly to change the rules. He pointed out the value of preserving office space in proximity to Union Station, one of the busiest transportation hubs in the country.

https://www.thestar.com/business/20...ers-could-last-at-least-two-more-decades.html

Knocking down office buildings cheaper

“It’s not as easy as people think it is. And there are only a handful of existing properties that would even be a candidate for it,” said Savoie, who is also a senior vice-president at Dorsay Development Corp.

In some cases, knocking the office buildings down and putting up something new makes more sense, said Savoie. In a few cases, retrofitting it to convert it into a condo building is more tempting, she added.

“Sometimes it would be cheaper just to take it down and start from scratch. But sometimes it has great structure and great bones and you have a lot to work with,” said Savoie.

Still, she added, most municipalities have strict rules about converting commercial buildings into housing, or even tearing one down and replacing it with a condo tower. Many municipalities also require an office or employment component in any new mixed-use development. That means, Savoie argued, that developers are being asked to build office space for which there’s no demand and that governments need to re-examine zoning policies.

Veteran real estate analyst John Andrew said encouraging a pipeline of new office construction may have made sense in a pre-COVID world, but agreed that governments now need to shift their thinking. Anything, he said, is better than offices sitting empty.

“If a developer wants to build condos, for god’s sake, let them build condos because at least it’s going to put more people downtown,” said Andrew, a retired real estate professor from the Smith School of Business at Queen’s University. Most excess office space can’t be converted into residential buildings for engineering reasons, Andrew added. That means, if zoning rules are eventually loosened, Toronto could see wrecking balls coming out in a big way.

“We’re going to start to see a tremendous wave of demolition happening. Companies are going to say ‘you know what? It’s worth the cost and the delay to completely level this building to the ground and start new,’” said Andrew.

“I think we’re going to start to see 50-storey office buildings being demolished.”

Last edited: