Toronto’s affordable housing crisis is no secret. The number of families on waiting lists for subsidized housing increased by 1.6 per cent this year, the average home price increased by 18 per cent, and the Toronto Community Housing Corporation (TCHC) faces a $2.6-billion repair backlog. Combine that with statistics that project the GTA’s population to skyrocket by nearly 43 per cent in the next two decades, and the term "crisis" appears almost euphemistic.

Ontario, in turn, updated the Long-Term Affordable Housing Strategy this March, mandating that "every person has an affordable, suitable and adequate home." For Toronto, the updated Strategy comes in the wake of the City's failure to stay on track with regard to its goal of building 10,000 affordable rental homes by 2020 under the Housing Opportunities Toronto Action Plan 2010-2020. The amended Strategy’s recommendations elaborated a framework for a portable housing benefit, a long-term commitment to stable funding, and, importantly, proposed Inclusionary Zoning (IZ) legislation.

Toronto's growing skyline, image by Jack Landau

Toronto's growing skyline, image by Jack Landau

"Ninety-five percent of housing in Ontario is provided by the private market. This works for most Ontarians, but because of rising housing prices and rents, an increasing number of families and individuals are finding it difficult to find housing they can afford," Conrad Spezowka, a media relations officer at the Ministry of Municipal Affairs, told UrbanToronto (UT) in an email. "The private sector needs to be engaged in the development of a broader range and mix of housing, including affordable housing, to assist in meeting people’s needs," Spezowka argued.

IZ, regulated at the municipal level, attempts to do just that. Used in jurisdictions around the world, IZ legislation requires private developers to set aside a portion of below-market units (often somewhere between 10 and 30 per cent) to boost affordable housing supply and produce socio-economically diverse neighbourhoods.

In May, Ontario introduced Bill 204, The Promoting Affordable Housing Act, which would enable municipalities to implement IZ. Since Bill 204’s first reading, Toronto’s urban developers, affordable housing advocates, and policy wonks, have done somersaults about the implications of IZ for the City. Since then, Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne has prorogued the legislature so as to rejig the province’s priorities ahead of the 2017 election, effectively dropping Bill 204 from the Order Paper. "The Bill will be reintroduced in the very near future," however, Spezowka noted.

Despite Wynne’s announcement, Toronto’s debate around affordable housing and IZ has not dampened. "We have a real opportunity here to move away from centralized control toward developing a dynamic regulatory system that can apply across a city as socio-economically diverse as Toronto," Kendra Teale FitzRandolph, Manager at NXT City, told UT in an email.

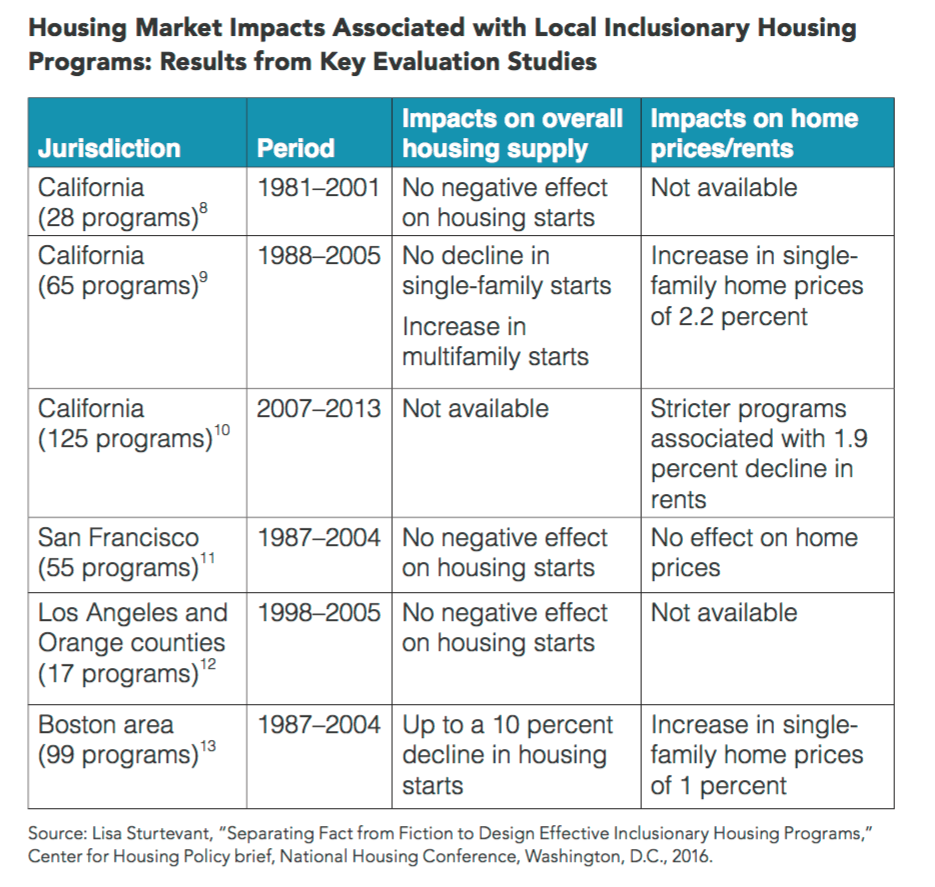

In a lecture hosted by the Urban Land Institute on Thursday, September 8th, Michael Wilkerson, Senior Economist with ECONorthwest, argued that—taken as one tool in the housing policy toolkit—IZ policies effectively harness the free market to increase affordable housing supply where units would otherwise not be built. Reading from a recent report co-authored by the Urban Land Institute and ECONorthwest, Wilkerson argued that without Canadian data, Toronto would do well to learn from its neighbours down south. Over 500 municipalities across the United States have enforced IZ policies in various iterations since the 1980s.

An evaluation of housing market impacts associated with IZ legislation in the US, image via ULI/ECONorthwest

An evaluation of housing market impacts associated with IZ legislation in the US, image via ULI/ECONorthwest

Wilkerson noted that U.S. data provides important policy conclusions, most notably that mandatory IZ legislation is often more effective than voluntary policies, like Toronto’s Open Door program. Mandatory IZ legislation is generally combined with a concoction of incentives for developers to offset negative impacts.

Potential incentives include direct construction subsidies to offset construction costs, reduced parking requirements, opt-out payment options, tax abatements (a less common type of incentive), and density bonuses, which are the most common form of incentive for both mandatory and voluntary IZ policies.

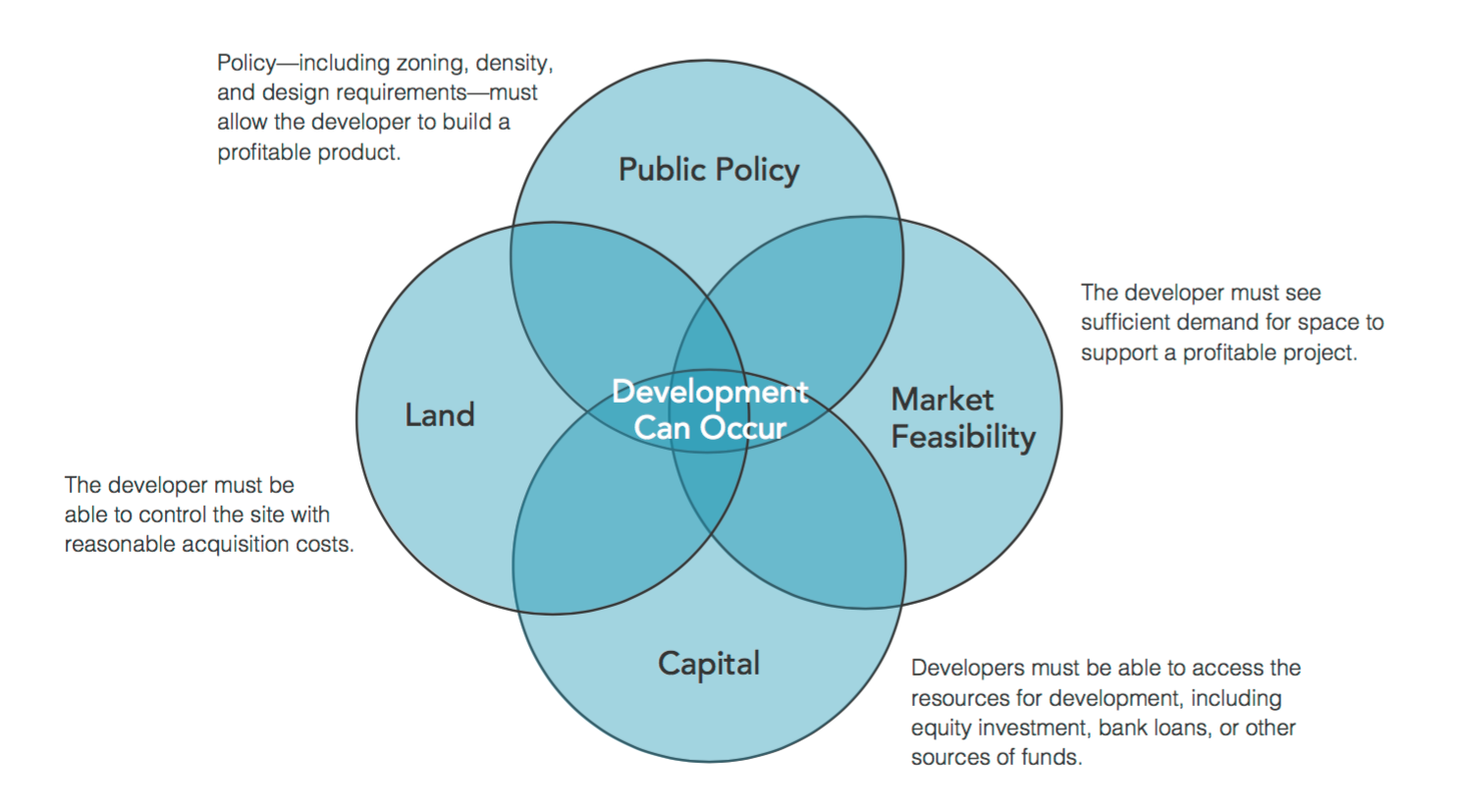

An overview of the necessary factors to make development feasible, image via ULI/ECONorthwest

An overview of the necessary factors to make development feasible, image via ULI/ECONorthwest

Wilkerson also described how IZ depends on local market-rate development. In neighbourhoods with high market-rate development, IZ policies are able to generate the most below-market units, often without negatively affecting home prices, rents, or—crucially—new housing starts.

Most importantly, IZ is an effective policy measure when it comes to creating socio-economically diverse neighbourhoods. “IZ has shown to help communities and neighbourhoods to become stronger, more vital and more diverse and inclusive through housing choices that includes affordable housing. When people have access to stable, affordable places they can call home, it opens up possibilities for better education, health, and work,” Spezowka said.

In line with Wilkerson’s analysis, Ontario’s Bill 204 outlined a mandatory policy aimed at increasing affordable housing supply, which is defined as a home that is at least 10 per cent below average market value, or—in terms of households and/or individuals—as homes that cost no more than than 30 per cent of gross annual income.

Following a discussion guide, interested parties and organizations were asked to submit their input on the legislation by August 16. On August 9, the City of Toronto submitted an official response to Bill 204, strongly opposing the legislation.

While the response acknowledged that Bill 204 is a "welcome step in providing the planning and program tools to create more affordable housing," the City recommended that moving forward, the province would do well to provide “predictable, clear and consistently applied” policy direction, ensure policy flexibility, and emphasize lateral partnerships between all levels of government, non-profit housing sector actors, housing advocates, the development community, and the public.

For Ward 18 City Councillor and Housing Advocate Ana Bailão, Bill 204 presented an impossible choice for city-builders: Section 37 benefits or affordable housing. Section 37 of Toronto’s Planning Act allows the City to negotiate with developers who wish to build denser or taller buildings than the zoning laws permit and exchange building permits for “community benefits,” including parks, libraries, daycares, roads, streetscapes, public art, community centres, and, sometimes, affordable housing. The Section 37 agreements are approved by City Council, and funds are directed by the appropriate City Councillor.

Ana Bailão speaking about affordable housing at CityPlace's Block 36 North in 2015, image by Stefan Novakovic

Ana Bailão speaking about affordable housing at CityPlace's Block 36 North in 2015, image by Stefan Novakovic

“It’s a choice that you shouldn’t have to make,” Bailão told UT in a telephone interview. “The reality is that the pressure is still there. You’re still building those units, you’re still creating the pressure on the library or daycare or parks system, and you need [Section 37] funds to deal with that,” Bailão said.

Bill 204 would have restricted the City from reaping Section 37 benefits on top of inclusionary zoning. Bailão argued that councillors could use Section 37 benefits to secure affordable housing in conjunction with the Open Door policy, which provides incentives to developers willing to build affordable housing.

In addition to conflicting with Section 37 benefits, Bill 204 might have also prevented municipalities from receiving cash-in-lieu or negotiating the construction of off-site affordable homes in circumstances where providing and operating affordable housing is unsustainable for developers.

Nonetheless, Bailão argued that the City’s problems with Bill 204 are ultimately not irreconcilable. "There’s no reason to have to choose between one or the other," she explained. Most important for Bailão is that affordable housing policy hits the ground running. "We need to actually translate something into units. I don’t want to create a feel good policy and then have it not translate."

Affordable housing policies are always "complex legislation," Bailão explained. "And in order to be successfully implemented, we need to be thoughtful and careful. [Affordable housing] is essential in a market like ours, and is essential if we want to continue to have a city that prides itself on the diversity, inclusiveness and opportunity that we give our residents."

***

What are your thoughts on Bill 204 and Toronto's response to the province? Will inclusionary zoning help Toronto deal with the affordable housing crisis or interfere with the City's ability to secure Section 37 benefits? How can we reconcile Section 37 with IZ legislation? Weigh into the conversation by leaving a comment below.

1.6K

1.6K