Ontario's Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe estimates the region's population will grow to 13.5 million people by 2041. Municipalities within the Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH) have historically accommodated growth via low-density greenfield development on the fringes of urban centres or high-density developments in downtown and inner-city neighbourhoods. Both approaches come with their own host of problems. Urban sprawl threatens arable land and the natural environment, while dense and tall development puts pressure on municipal infrastructure and services, and provides limited affordable family-friendly housing options. Density Done Right, a new report released this week by the Ryerson City Building Institute, suggests these two approaches are not sustainable, and a new pattern of housing development must be implemented to ensure a healthy, livable and affordable region for all residents.

Townhomes and high-rises in South Etobicoke, image by Marc Mitanis

Townhomes and high-rises in South Etobicoke, image by Marc Mitanis

The dangers of urban sprawl are largely recognized—paving over farmland and natural ecosystems contributes towards long commuting times, increased greenhouse gas emissions, and a greater financial burden for municipalities to service these low-density communities.

The costs of hyper-concentrated development are also starting to become tangible. Recently completed tall buildings are generally devoid of units suitable for larger households, and too much density in one place can overburden local infrastructure. The issue is particularly acute in Toronto's Yonge and Eglinton neighbourhood, where the Midtown in Focus study attempts to ensure infrastructure capacity keeps pace with development.

The Missing Middle, image via Ryerson City Building Institute

The Missing Middle, image via Ryerson City Building Institute

Planners in the GGH have opined about the elusive "missing middle" across multiple forums in recent years. The term was first coined by American design firm Opticos, referring to housing two to three storeys in height that demonstrated compatibility with single-detached and walkable neighbourhoods. When applied to the GTHA, the concept generally alludes to gentle- and medium-density housing types like mid-rises and townhouses. More recently, the term has taken on an affordability angle, referring to middle-income families falling between subsidized and current market-rate housing.

What distributed density could look like in an existing neighbourhood, image via Ryerson City Building Institute

What distributed density could look like in an existing neighbourhood, image via Ryerson City Building Institute

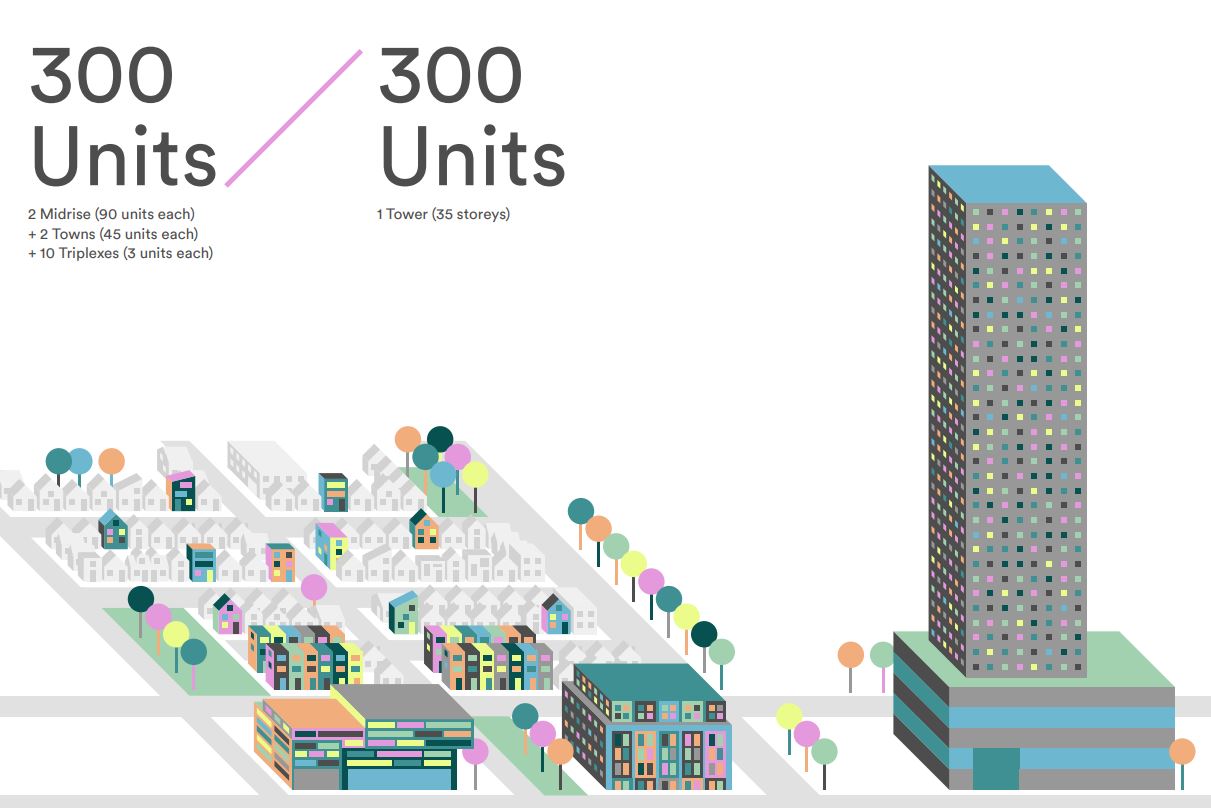

The Ryerson City Building Institute recommends "distributed density" as an alternative to the predominant "tall and sprawl" pattern of development in the region. The Institute suggests that distributing low-, medium- and high-density residential development throughout urbanized areas in the GGH would address the negative impacts of hyper-concentrated development, provide a greater range of housing options, and minimize the reliance on urban sprawl as a method of providing family-sized homes.

An opportunity for the missing middle amid single-detached homes and apartments, image by Jack Landau

An opportunity for the missing middle amid single-detached homes and apartments, image by Jack Landau

The Institute advocates for a range of scales at major transit hubs, mid-rise buildings along transit corridors, avenues and main streets, walk-up apartment buildings and townhouses in existing residential neighbourhoods, and accessory dwelling units like laneway suites or backyard suites in low-rise areas. The report also proposes converting existing single-detached dwellings into multi-unit residences to add gentle density without significantly altering the built form and scale of a mature neigbourhood. Many of these solutions would require changes to municipal zoning bylaws, but progress is gradually being made. The City of Toronto recently amended its Official Plan and zoning regulations to permit laneway suites in low-rise residential areas, the City of Hamilton amended its planning policies to allow more density downtown, and the City of Kitchener recently adopted a new zoning bylaw to build granny flats, tiny houses and carriage houses on residential lots.

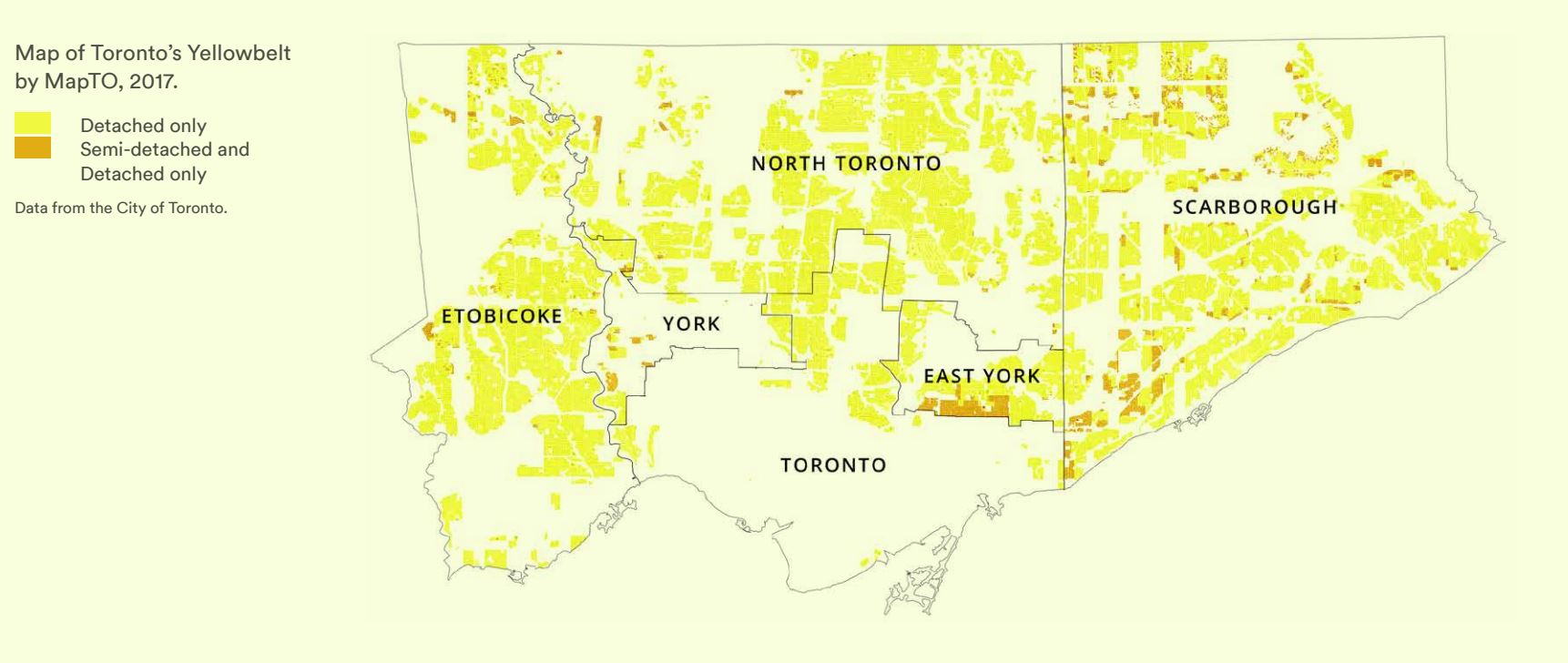

Toronto's Yellowbelt in 2017, image by MapTO via Ryerson City Building Institute

Toronto's Yellowbelt in 2017, image by MapTO via Ryerson City Building Institute

Several municipalities in the GGH restrict multi-unit housing typologies to small urban footprints through their respective zoning bylaws, enshrining the single-detached home as the primary—and often only—allowable housing option in many neighbourhoods. These large swaths of detached- and semi-detached-only areas are known as the "Yellowbelt," which references the colour assigned to these lands on municipal zoning maps.

An alternative to tall: accommodating 300 units by distributing density, image via Ryerson City Building Institute

An alternative to tall: accommodating 300 units by distributing density, image via Ryerson City Building Institute

A number of recent studies have proved that cities in the GGH have plenty of room to grow. According to Finding the Missing Middle in the GTHA, a 2018 report released by the Ryerson City Building Institute, the City of Mississauga could accommodate over 174,000 new housing units in low- and mid-rise buildings within the existing urban footprint without adding density to single-detached residential neighbourhoods. Research conducted by Ryerson University's Centre for Research and Land Development found that townhouse development along rapid transit corridors could sufficiently accommodate all the province's expected population growth over a 24-year period. And another study by architecture firm Studio JCI puts forth the idea of adjusting zoning to transform single-family homes into multi-family buildings containing three to five units. Studio JCI estimates that transitioning just one percent of Toronto's existing 1.1 million households could create approximately 44,000 new housing units. Converting existing low-rise housing stock into multi-family units would also help address the issue of empty bedrooms in the province; the Canadian Centre for Economic Analysis finds that nearly two-thirds of Ontarians are over-housed, resulting in roughly five million empty bedrooms across the province.

Highrises comprise the bulk of new housing construction in Toronto, image by Marc Mitanis

Highrises comprise the bulk of new housing construction in Toronto, image by Marc Mitanis

The report also explains that distributed density can rescue neighbourhoods experiencing declining populations due in part to demographic changes. Introducing gentle forms of density can support the health and vitality of communities and their schools, services and local retailers. With greater intensification and population density comes improved transit service, reducing private automobile dependence.

The Ryerson City Building Institute hopes Density Done Right will inform citizens and decision-makers to advocate for sustainable and healthy growth in municipalities within the GGH. The full report is available online for download.

* * *

UrbanToronto has a new way you can track projects through the planning process on a daily basis. Sign up for a free trial of our New Development Insider here.

8K

8K