The provincial government recently announced that it will not renew the subsidy that has provided riders with a $1.50 discount when transferring between GO Transit and the TTC for the last two years. This is very much a step in the wrong direction. While governments are in the midst of spending billions of dollars on big capital projects, the $18.5 million per year required to maintain the program is a comparative pittance. But its importance isn’t minor: Metrolinx’s GO RER vision is intending to transform the GO network from a peak period parking shuttle to downtown Toronto into a real transit system, and that will never be feasible unless GO and the TTC have a unified fare structure. Instead of cutting funding for a discounted fare, the province should be spending what is necessary—small in terms of overall transit spending—to fully unify the two agencies’ fares.

Presto fare gates, image by wyliepoon via Flickr

Presto fare gates, image by wyliepoon via Flickr

There are numerous communities in the City of Toronto that suffer from gruelling bus-and-subway transit trips that take over an hour to get downtown or across the city. They are furthermore disproportionately low-income and New Canadian communities, which desperately need better access to the services and opportunities in their city. And yet, in many cases, they have GO rail corridors running right through them that could slash their travel times in half or better. The problem is that the GO rail service is usually very limited—designed for peak period commuters to Union Station only—and the fare is prohibitively high. We have a tremendous infrastructure that could greatly improve the lives of hundreds of thousands of Torontonians, and we’re letting it lie mostly dormant because we won’t make the comparatively small operating funding investments required to improve the service and make the fares fair.

TTC streetcar, image by Adrian Badaraco via Flickr; GO trains, image by Randy Hoffmann via Flickr

TTC streetcar, image by Adrian Badaraco via Flickr; GO trains, image by Randy Hoffmann via Flickr

Let’s take an example. Residents of Malvern in Scarborough have some of the longest commutes in the city. To get downtown, it takes over an hour and a half by bus and subway. If the GO Stouffville line had frequent service, as is being planned with GO RER and SmartTrack, it would only be a 15-minute bus ride from Malvern to a station at Finch, followed by about a half-hour train ride downtown. This would mean a full hour-and-a-half every single day given back to Malvern residents, who would be able to spend that time with their families or on just about anything they would likely rather be doing than commuting. And it’s not just about downtown—people could transfer from the GO services to the subway or other buses, speeding trips to points all across the city. The trouble is, it’s never going to work if the one-way fare, on GO and TTC, is $9.22 as it is today. Few people will be willing to pay triple the TTC fare, even for such a significant time savings, and it’s a burden that falls especially hard on the low-income riders who are disproportionately located in communities like Malvern. Why should a rider on the subway pay $3.10, while a rider travelling the same distance on a GO rail route—which cost far less to build than the subway—pay three times as much?

TTC subway train, image by dtstuff9 via Flickr

TTC subway train, image by dtstuff9 via Flickr

The cost of better fare policy is small by the standards of what we spend on transit capital projects. Take Downsview Park Station on the new York subway extension, for example. It cost over $100 million to build and one of its major purposes is to accommodate connections between the subway and the GO Barrie Line. Yet its ridership remains low, because the cost of such a transfer is very high. The annual cost of the discounted transfer is less than one-fifth the cost of Downsview Park station alone, and it benefits riders transferring all across the system. We can get much better use out of the expensive infrastructure we have built and are building if we are willing to make small investments in fairer fare policies.

Downsview Park Station, image by Jack Landau

Downsview Park Station, image by Jack Landau

The amounts we are discussing are shockingly small. The half-price fare for connections cost $18.5 million per year. Presumably eliminating the transfer fare entirely shouldn’t cost too much more than double that amount. Furthermore, the previous provincial government’s promise to cut GO fares within the City of Toronto to $3 was projected to cost $30 million per year. It is therefore reasonable to assume that a comprehensive, region wide integrated fare system that allows every rider to use the mode that gets them where they need to go as quickly and efficiently as possible could be introduced for not much more than $100 million per year. The revenue generated by increased ridership would likely also offset some of that over time. In the context of the $40 billion+ transit plans for the region, that’s extremely affordable.

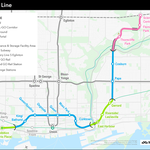

The optimal fare structure for the region is probably what I like to call the “Berlin Model.” It’s the best way to eliminate unfairness without forcing existing riders who are already struggling to make ends meet to pay more than they are today. Simply put, the GTA could be divided into A, B, and C zones, with the A zone roughly comprising the old City of Toronto, the B zone being the rest of the 416, and the C zone encompassing the inner 905 like Mississauga, Vaughan, and Markham. The basic ticket would be a two-zone ticket. That means that riders within the City of Toronto would still pay the same flat fare as they do today. Likewise, people commuting long distances from the 905 to downtown would pay for a three-zone ticket at a similar fare to what they pay today. Where there would be a huge difference is the resident of Rexdale who works in Vaughan. Even if she is only travelling a few kilometres, a transit trip across Steeles costs a whopping $6.98 one way. That’s simply punitive. Under the new system, she could buy a cheap two-zone ticket, which would greatly increase cross-boundary transit ridership. By incorporating GO services into the same basic fare structure, we would radically improve access access to jobs and services for much of the city, including many low income communities, who currently can only dream of riding the swift but unaffordable trains.

If this region is going to unlock the full benefits of its major capital investments on projects like GO RER, we need to move toward an integrated fare system that is affordable for riders and that does not punish people who transfer between modes or between agencies, or who ride across municipal boundaries. We can only hope the province will reconsider this decision and move toward funding a truly integrated fare structure. In the meantime, we can hope that Metrolinx, the TTC, and the City of Toronto will find a way to fund the continuation of the existing program out of their budgets.

* * *

UrbanToronto has a new way you can track projects through the planning process on a daily basis. Sign up for a free trial of our New Development Insider here.

5.8K

5.8K