For one evening, amidst the endless rush of new construction projects and planning proposals, the past was alive in Toronto. It was being celebrated at the 42nd Heritage Toronto Awards, which recognize achievements in both media and architecture.

Many of Monday night’s laureates and participants, however, maintained that this was not the only day of the year that the city’s heritage rose to the forefront of public consciousness. More than a celebration of individual projects, the awards ceremony and accompanying Kilbourn Lecture were a self-styled celebration of the rapidly growing awareness of heritage issues.

According to Heritage Toronto, the 61 projects nominated across five categories represented a 30 per cent increase over the previous year’s field.

324 Broadview, image by Building Arts

324 Broadview, image by Building Arts

Some of the awarded works were newly completed restorations or reuses of buildings that Torontonians may walk past on a regular basis. Building Arts Architects’ 324 Broadview office retains the façade of the Standard Bank of Canada branch that formerly occupied the site as well as its vault. The changes to The Don Jail, the evening’s other architectural award of excellence winner, are less visible from the street. On the inside, however, the formerly prescriptive space has been turned into a flexible administration building for Bridgepoint Active Healthcare. It’s usually a pejorative to describe an office as a jail, but this is the exception that proves the rule.

Other laureates highlighted heritage buildings that have been in plain sight for decades but are due for more recognition. Viljo Revell’s Toronto City Hall, which celebrated its 50th anniversary last year, was a locus of attention. Christopher Armstrong’s Civic Symbol: Creating Toronto's New City Hall, 1952-1966, an award of merit winner in the book category, chronicles the building’s construction, a story also told in the media award of excellence winner, the documentary Finn with an Oyster. (The film will be screening at the Gardiner Museum on November 3: you can get tickets here.)

As a civic monument, City Hall is also a reminder of the urban heritage that was razed in the building’s construction. The history of that area in its earlier days is the subject of the book award of excellence winner, The Ward: The Life and Loss of Toronto's First Immigrant Neighbourhood. Likewise, the Lakeshore Asylum Cemetery Project—winner of both the Etobicoke and Member’s Choice community heritage awards—seeks to draw attention to the forgotten chapter of the province’s treatment of psychiatric conditions. Other winners, like Jane’s Walk, The Friends of Fort York and Garrison Common, and David Wencer’s Torontoist’s history of Peter R. Lamb and Co. glue factory, all guided the public through different and less visible aspects of the city’s history.

Nathan Phillips Square and City Hall, image by Jack Landau

Nathan Phillips Square and City Hall, image by Jack Landau

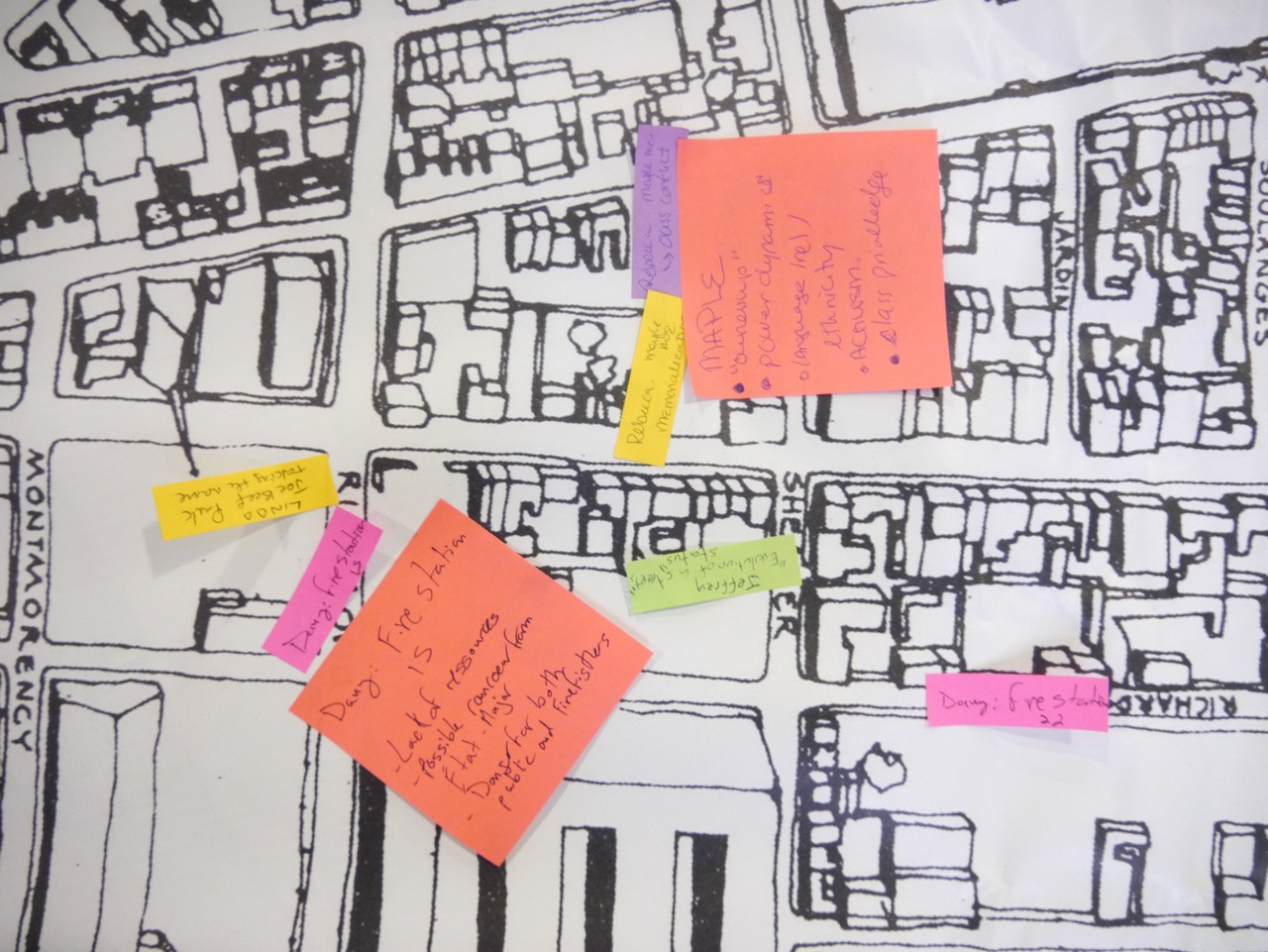

That latter entry, which emphasized the smell produced by the glue factory, echoed the 20th annual Kilbourn Lecture delivered by Concordia University’s Dr. Steven High. A researcher at the university’s Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling, High argued that the urban transformation brought about by deindustrialization affected the totality of residents’ sensory experiences. Changes to the urban landscape, he said, are often most apparent in terms of sound and smell. [Disclosure: the author’s father is COHDS’ current director.]

“Industrial heritage is about so much more than the physical remains of the mill or factory,” High said. “A noise that becomes a nuisance to some may be a delight to others—this is certainly true of train noise.”

In that way, sensory experience is at the heart of debates over transitioning neighbourhoods. By extension, focusing on these elements affects the types of stories that heritage work centres. Whereas “ruin-gazing” focuses on the visual aspect of de-industrialized sites, it can erase the experiences of former and current residents. Smells and sounds, on the other hand, foreground the experiences of people who were actually there. This, High said, leads to a more inclusive approach to history: “The focus on the beauty of abandoned buildings and not the humanity of those displaced raises questions about voyeurism.”

Some of that sensory heritage can no longer be experienced. The event’s host, former CBC Fresh Air host Mary Ito, grew up near an urban slaughterhouse. ““When I was a kid on a certain day,” she recalled after High’s talk, “you would get that sense.” The area’s dominant industry could be smelled more than seen.

Mapping post-industrial cities, image by COHDS

Mapping post-industrial cities, image by COHDS

Toronto’s history, however, does not simply go back to the days of big industry. Carolyn King, the former Chief of the Mississaugas on the New Credit First Nation and winner of Heritage Toronto’s Special Achievement award, reminded the capacity crowd of 600 that any built history of the city has to go further back than the 19th century. “We can’t change history,” she said, “but we can change the perspective and interpretation of that history.”

King established the Moccasin Identifier Project, which publicly recognizes sites in cities with painted moccasin symbols to reflect tribes that once lived there.

All of these levels of history and symbolism coexist in the urban space, some more easily than others. The Heritage Toronto Awards is a recognition of all the work being done to bring this history to the surface, but it is also a reminder of how much work has yet to be done.

***

While the Heritage Toronto Awards recognize completed works, a number of projects with heritage implications remain in progress. We will keep you updated as these works continue. Want to share your thoughts? Leave a comment in the space below this page, or join the conversations in our Forum.

1.2K

1.2K