Jonathan English's new column on transit continues following last week's inaugural article on the OneCity transit plan. This week we look at CityRail, a concept which would bring rapid transit to underserved areas of Toronto and across the GTA sooner and at less cost than other methods. Could a version of this concept get traction here?

This article is shared with the blog Transit Futures.

The introduction of genuine regional rail in the GTA would be the most revolutionary transit improvement in the region since the opening of the original subway in 1954. Toronto woefully underuses its comprehensive network of rail corridors connecting all of its suburbs with the central city and with each other. Right now, most corridors see about a dozen mammoth trains a day shuttling commuters from vast parking fields to downtown office buildings. Regional rail is an entirely different type of service in the same corridors, more akin to a subway or other rapid transit line than to locomotive-hauled GO bi-levels. There are several key characteristics that define regional rail: frequent service all day and every day; full fare integration and seamless connections with local transit; and electrified multiple unit trains that allow fast acceleration and frequent stops.

CityRail Plan, cartography by Craig White

CityRail Plan, cartography by Craig White

THE CITYRAIL CONCEPT

Genuine regional rail will not occur as a result of piecemeal improvement of existing GO service. It must be developed through a comprehensive plan that guides all of the improvements required to achieve a desired standard of service: the CityRail concept. GO currently adds trains as demand requires and as freight railways permit. This is fine for a commuter service, but it’s not how rapid transit works. Imagine if the TTC cut back service on the subway to every half hour on Sundays because the trains weren’t running full. CityRail establishes the goal of real rapid transit service throughout the GTA and describes the necessary infrastructure improvements that will be required to achieve it. This clear final product makes the promotion of the concept much easier for transit agencies, both to the general public and to higher levels of government.

The initial CityRail concept involves the creation of rapid transit lines in all of the existing GO Transit rail corridors out to the edge of the urban area. Riders on CityRail lines will enjoy a minimum standard of service on all lines.

- CityRail would have trains at least every 15 minutes from morning until late night every day, including weekends, so that riders can go to a station without consulting a schedule and know that a train will arrive shortly. This allows the system to be used as a rapid transit backbone in both Toronto and the 905 suburban municipalities.

- CityRail services would have fully integrated fares with local transit service. Riders would transfer to and from CityRail as seamlessly as they currently do between TTC subways and buses. Fares would be the same for a given trip regardless of the mode chosen. Local transit routes would be routed into regional rail stations as they currently are to subway stations.

- CityRail trains would be operated with electric multiple units that produce no air emissions and accelerate far more rapidly than existing GO Trains, permitting frequent rapid-transit-style stops without longer travel times than GO services.

The Paris RER (Source: RATP)

The Munich S-Bahn (Photo by Florian Derwarf)

THE NECESSARY INFRASTRUCTURE

In order to achieve the service goals of CityRail, a substantial infrastructure investment would be necessary. However, the cost would be mitigated by the fact that little or no expensive underground construction would be required, the corridors and most stations are already in place, and off-the-shelf technologies and equipment that has been proven in regional rail systems around the world could be used.

- The most basic requirements for CityRail are dedicated, double-track lines in all corridors that would reliably permit rapid transit frequency. Many of GO Transit’s routes already have plans for additional tracks that could meet this goal, particularly the Weston corridor, but they aren't being dedicated to the exclusive use of regional rail service. Near the city centre, multiple lines could share a pair of tracks as they do in most international applications of regional rail. Metrolinx now owns many of its corridors outright, so that it could easily convert them for CityRail. Other corridors that are still owned by freight railways (most notably the Milton Line) would force the construction of a parallel pair of tracks, similar to the GO Sub line built in the early 1990s between Pickering and Oshawa. Most level crossings would also need to be eliminated.

- CityRail requires advanced signalling to permit high-frequency operation. European countries have invested billions of dollars in the development of technologies for the ERTMS signalling standard, which is rapidly becoming the standard around the world outside North America. It would be impossible for North American transit operators to even approach the level of research and investment dedicated to ERTMS, and the adoption of the ERTMS standard would limit costs through the purchase of off-the-shelf equipment from multiple competing suppliers. While CityRail would be pioneering this new technology in North America, it is worthwhile as it would eliminate the limitations of relying on unique homegrown North American signalling systems. ERTMS allows the operation of trains as frequently as every 90 seconds; effectively the only limitation is maintaining safe braking distance between trains.

- CityRail will operate with attractive, modern electric multiple unit (EMU) trains much like those pictured above. EMUs have faster acceleration than locomotive-hauled trains, permitting frequent stops without sacrificing travel times. They are the standard on all international applications of regional rail. The trains will have comfortable seating for long-distance riders while also accommodating standees for those taking shorter trips at peak periods. They will also have multiple doors per car to speed loading and unloading, one of the major frequency limitations on current GO trains. Trains would be off-the-shelf designs with proven reliability in service on regional rail networks in Europe or Asia. Though they would not be compatible with current FRA/Transport Canada safety regulations, the agencies are already exploring the granting of waivers for the operation of European equipment in North America in areas with advanced signalling systems to prevent crashes. Ottawa has already received a waiver to operate its O-Train, which uses unmodified German rail equipment built by Bombardier.

- CityRail stations will need to be rebuilt with high platforms so that passengers do not need to climb steps to board the train. This both speeds loading and unloading, and improves wheelchair accessibility. Stations would be designed for seamless connections with local services, particularly where CityRail lines cross other rapid transit routes. Bloor Street/Dundas West and Main Street stations would be major transfer points, and the latter would receive a dedicated moving walkway connection. Most stations would include a small bus terminal, similar to those at TTC subway stations.

- As the hub of the CityRail system, Union Station would need special attention. CityRail could actually reduce the pressure on Union Station by using smaller trains at higher frequency. Nevertheless, the current platforms are narrower than would be ideal. The current reconstruction will add many new access points to the platforms, which will allow crowds to disperse quickly. Unfortunately, despite digging a vast cavern under the station, no effort was made to rearrange the columns supporting the tracks so that much wider platforms could be created. It may still be possible to shift tracks by cantilevering them from the existing columns, but that would require detailed engineering study. If not, some platforms could be widened through the removal of several tracks. This would not necessarily be a problem, as faster loading and unloading combined with advanced signalling systems could ensure that a substantially larger number of trains could be accommodated than with the existing arrangement. A costlier alternative would include the construction of underground rail platforms either under Union Station or on a different alignment through the downtown core. Shifting the time-consuming process of turning trains away from Union Station entirely would also mitigate capacity limitations. All eastern GTA lines would be combined with lines in the west, so that trips from Markham, for example, would continue onto the Milton line. Trains from the western GTA not continuing east could be turned at a spacious new Cherry Street station built on the site of the Don Yard.

- All CityRail lines would be electrified with overhead catenary at 25kv AC, which is the international standard. This would eliminate pollution from trains passing through urban neighbourhoods, reduce noise, and improve acceleration and travel times.

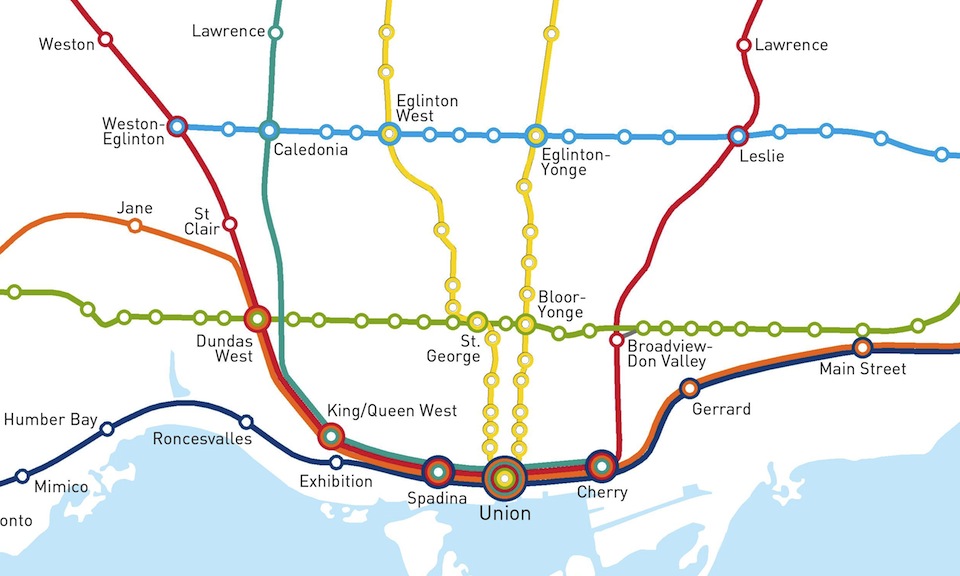

CityRail Plan central area, cartography by Craig White

CityRail Plan central area, cartography by Craig White

The first phase of CityRail would involve the existing GO corridors. There are multiple additional corridors that could greatly benefit from CityRail service, including one to Bolton through Woodbridge, to North Pickering through Agincourt, and to Brampton through Meadowvale. The North Toronto corridor through Summerhill Station would also be very useful for passengers not destined to the downtown core. A potential enhancement of the CityRail concept would include short diversions from existing corridors to serve major destinations. For example, CityRail could leave the Milton line at Cooksville, run up Hurontario to Mississauga City Centre and from there west along the 403 to re-join the existing corridor. Pearson Airport could also benefit from a diversion of the Georgetown Line, which could be shared with other operators including VIA and a premium Airport Express service.

CityRail would not only extend rapid transit to many unserved areas, but it would also provide a kind of express subway service for many trips. For example, a person from Mississauga going to the University of Toronto could take a bus to the closest CityRail stop, then have a much faster trip than the Bloor-Danforth line to Dundas West station, where they could transfer to the subway to take them to their final destination. People in the West Don Lands and Port Lands would enjoy trains every few minutes to take them from Cherry Street non-stop to the heart of downtown.

INTERNATIONAL EXAMPLES

Genuine regional rail is virtually non-existent in North America, but it is common in other parts of the world. Some of the most well known examples are the RER in Paris and the S-Bahn systems in most major German-speaking cities. Many major European cities had multiple historic train stations serving lines from different parts of the country. This was not a serious issue for intercity trips, but for passengers from the suburbs the peripheral stations required inconvenient transfers and overloaded the local transit system. As a solution, cities like Munich and Paris built tunnels in the postwar period to connect the regional services of the different stations. These tunnels passed through the city centres and permitted the inclusion of stations adjacent to some of the most important destinations. The Line A of the RER in Paris is served by trains every two minutes carrying more than 50,000 people per peak hour, making it the busiest urban rail route in Europe. The ridership of regional rail lines in Japan is even more extraordinary: the Yamanote Line, a 38km loop around central Tokyo, carries significantly more people than the entire London Underground.

Several cities are also implementing new regional rail. Brussels is developing a 350km RER system, including station reconstruction, quadruple-tracking main corridors, and a new tunnel. The total cost will be €2.173 billion (C$2.8 billion), which is half the cost of the Eglinton-Crosstown LRT. Paris is expanding its own RER system with a new line to relieve the Line A. London is currently building a massive new “+”-shaped regional rail system with its Crossrail and Thameslink projects. Denver will be the first to introduce regional rail to North America as part of its FasTracks program. Ottawa’s O-Train is a small-scale example of regional rail, built for the shockingly low cost of $21 million.

* * *

The CityRail concept would bring real rapid transit to the entire region, dramatically shortening travel times and improving the attractiveness of transit in the suburbs. It is much faster and more reliable than light rail in the middle of the street, and much less expensive than underground rapid transit. The region is blessed with an expansive network of rail corridors that, linked with local transit, could cost-effectively extend rapid transit deep into the suburbs and into transit-deprived areas of the 416. CityRail could transform transit in the GTA and serve as a model for the rest of North America.

ADDENDUM: The CityRail concept would fit very well into the existing transit proposals, such as The Big Move and OneCity. Both have already explored, at least in vague terms, a form of regional rail. The Big Move included "Express Rail" on the Georgetown and Richmond Hill corridors, while OneCity talked about a similar approach in the Georgetown and Stouffville corridors within the City of Toronto. Of course, both approaches pose problems for the development of CityRail-style regional rail. The Big Move talked about Express Rail, but while Metrolinx is investing hundreds of millions of dollars in upgrading existing GO corridors, there are no comprehensive plans for how these improvements will lead to an outcome of real regional rail like CityRail. Instead, they seem to pave the way for gradually increased frequencies of standard GO trains without any kind of fare integration. That is a real missed opportunity. Equally, regional rail must be planned and developed with a regional scope. CityRail's benefits are even greater in the 905 suburbs, where no rapid transit backbone currently exists, than they are in the 416. Unfortunately, OneCity's funding approach limits it to the boundaries of the City of Toronto. It makes no sense to stop regional rail at Steeles, so a regional financing approach is essential.

CityRail isn't the solution to every transit problem in Toronto. Local transit improvements, particularly the Downtown Relief Line, are necessary to serve trips that won't be adequately served by the CityRail corridors. Suburb-to-suburb trips would benefit greatly from crosstown routes like a 407 transitway. CityRail would not solve every transit problem, but it would serve as the backbone of transit throughout the GTA.

4.2K

4.2K