fiendishlibrarian

Active Member

The Leaside Towers, yes, among my favourites as well! Almost got a place there when I worked at UTSC. They seem to me like buildings from the future circ. 1968 just plopped in the middle of nowhere. I'll add to that by saying their midtown cousin and my current abode, the Manulife Centre, is also amongst my faves. I agree with the other picks here but I'll throw in a few more:

- Park Plaza (the original, now the Hyatt), Avenue at Bloor. Love the massing at street level, and it just says "big city hotel" to me, even moreso than the Royal York

- University College. I discover something new about it everytime I look at it, and I had classes in there (and worked there) for a number of years.

- The Ross Building at York. It has an unapologetic, stern austerity to it I've always loved even if the classrooms in it are cubbyholes.

- Canada Life. A strange, admirable, and unique instance of an attempt at grandeur in this city that seems more common in Montreal or Chicago.

- The Colonnade. Still largely intact in its Mad Men-era glory. I feel like I should have a jacket and tie on when I walk in there. Sophistication defined.

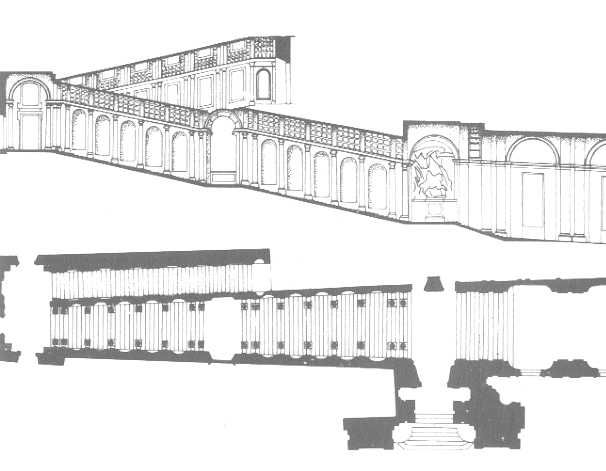

- Scarborough College. Like the Colonnade, still largely intact from its construction (even its floor tiles haven't been changed), with some really unique spaces and uses of form.

- 10 and 20 Avoca Avenue. Something about their clean, uninterrupted lines have always appealed to me. And they are apparently gorgeous apartments on the inside. This building, as well as the Forest Hill complex (especially 135 Antibes) at Antibes Drive in North York and the Spadina Hill towers at St. Clair, to me all capture the brief moment in time of glamorous, urbane apartment living in Toronto. If you've ever watched the 1970s Bob Newhart show you'll know what I mean.

- The original Commerce Court, East, 1931. As close as we'll get to American Radiator.

Edit: I'm going to throw Robarts in there, but Robarts at a particular time in the early to mid-90's when all of the original signage and fixtures were largely still intact from when the building was completed (I remember the card catalogue!). Lousy as a working library (which it was not designed for as originally no one was allowed past the second floor) but it appeals to me all the same. Honourable mention to Scott Library at York for similar reasons.

- Park Plaza (the original, now the Hyatt), Avenue at Bloor. Love the massing at street level, and it just says "big city hotel" to me, even moreso than the Royal York

- University College. I discover something new about it everytime I look at it, and I had classes in there (and worked there) for a number of years.

- The Ross Building at York. It has an unapologetic, stern austerity to it I've always loved even if the classrooms in it are cubbyholes.

- Canada Life. A strange, admirable, and unique instance of an attempt at grandeur in this city that seems more common in Montreal or Chicago.

- The Colonnade. Still largely intact in its Mad Men-era glory. I feel like I should have a jacket and tie on when I walk in there. Sophistication defined.

- Scarborough College. Like the Colonnade, still largely intact from its construction (even its floor tiles haven't been changed), with some really unique spaces and uses of form.

- 10 and 20 Avoca Avenue. Something about their clean, uninterrupted lines have always appealed to me. And they are apparently gorgeous apartments on the inside. This building, as well as the Forest Hill complex (especially 135 Antibes) at Antibes Drive in North York and the Spadina Hill towers at St. Clair, to me all capture the brief moment in time of glamorous, urbane apartment living in Toronto. If you've ever watched the 1970s Bob Newhart show you'll know what I mean.

- The original Commerce Court, East, 1931. As close as we'll get to American Radiator.

Edit: I'm going to throw Robarts in there, but Robarts at a particular time in the early to mid-90's when all of the original signage and fixtures were largely still intact from when the building was completed (I remember the card catalogue!). Lousy as a working library (which it was not designed for as originally no one was allowed past the second floor) but it appeals to me all the same. Honourable mention to Scott Library at York for similar reasons.

Last edited: