July 27, 2018 was a dark day for democracy in Toronto. Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s stunning decision to slash the size of Toronto City Council from 47 to 25 councillors with the Fall 2018 municipal election already underway has upended the local political landscape, drawing vociferous criticism from across the political spectrum. Ford’s reckless move has launched Toronto politics into a state of chaos reminiscent of that during his late brother’s infamous mayoralty.

In trying to sell his decision, Ford has opted for the type of simplistic populist trope we have come to expect from him and others like him: “No one has ever said to me, ‘Doug, we need more politicians.’” The truth he withholds, of course, is that millions of Torontonians will have less political representation than they currently enjoy.

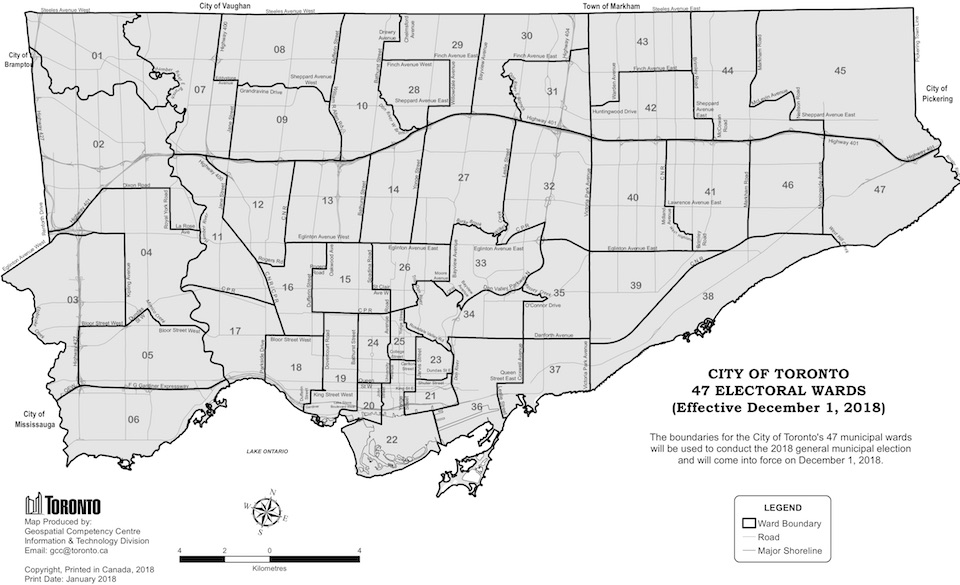

The question of how many councillors Toronto should have was in the air before Ford threw his newly acquired political weight into the mix, having been the subject of a contentious Ontario Municipal Board (the former OMB, now known as the Local Planning Appeal Tribunal, or LPAT) decision which affirmed the redrawing of the boundaries of many of Toronto’s wards and the expansion of City Council from 44 to 47 councillors in time for the October 2018 election.

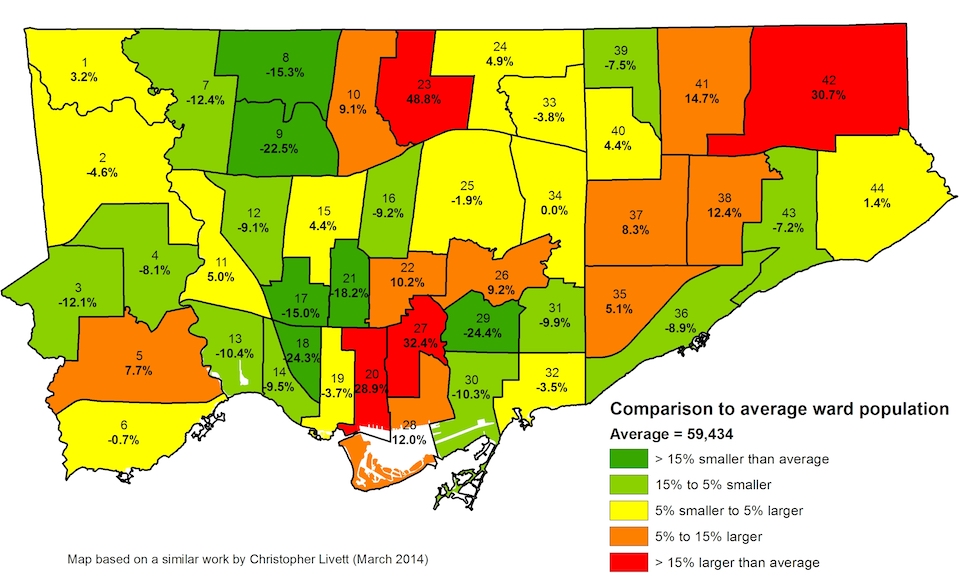

The genesis of the decision to increase the size of City Council was the Toronto Ward Boundary Review, 2014-2016 (TWBR), which was initiated by City Council in response to Toronto’s population explosion over the last number of years and examined whether this growth had led to inequities in political representation across the city. As a result of both organic factors and a combination of provincial and municipal planning and growth policies, Toronto’s population growth has not been evenly distributed — some wards had grown 45% above the average ward population, and the City was “concerned that the value of a resident’s vote may not be equal across all wards if this trend continued”.

2014-2018 wards, populations compared to average, image courtesy of Sean Marshall

2014-2018 wards, populations compared to average, image courtesy of Sean Marshall

The TWBR was conducted by a team of independent expert consultants chosen by the City after a competitive RFP process, and encompassed interviews with the mayor and councillors and multiple rounds of public consultations over a period of more than two years. The process was complex, analytically rigorous, highly consultative, and democratic, standing in stark contrast to Premier Ford’s anti-intellectual, autocratic power grab.

City Council adopted the core TWBR recommendations in November 2016. Council’s decision was then appealed at the OMB by (among others) Etobicoke councillor Justin Di Ciano — a political ally of Mayor John Tory — and noted Council rabble rouser and loudmouth, Giorgio Mammoliti, who both stood to lose a degree of political power as a result of the decision. Di Ciano’s camp argued in favour of the 25-ward option that Ford would impose many months later.

The appeal was unsuccessful, with the majority members writing: “...there are no clear and compelling reasons to interfere with the decision of Council” and summarizing that “effective representation is the primary goal and the board finds that the 47-ward structure, reflected in the by-laws, does achieve that goal”. The TWBR’s recommendations aimed to maintain the average ward population at 61,000 people, meaning each councillor would represent 61,000 constituents. With 25 councillors under Ford’s plan, each councillor would represent more than 100,000 constituents.

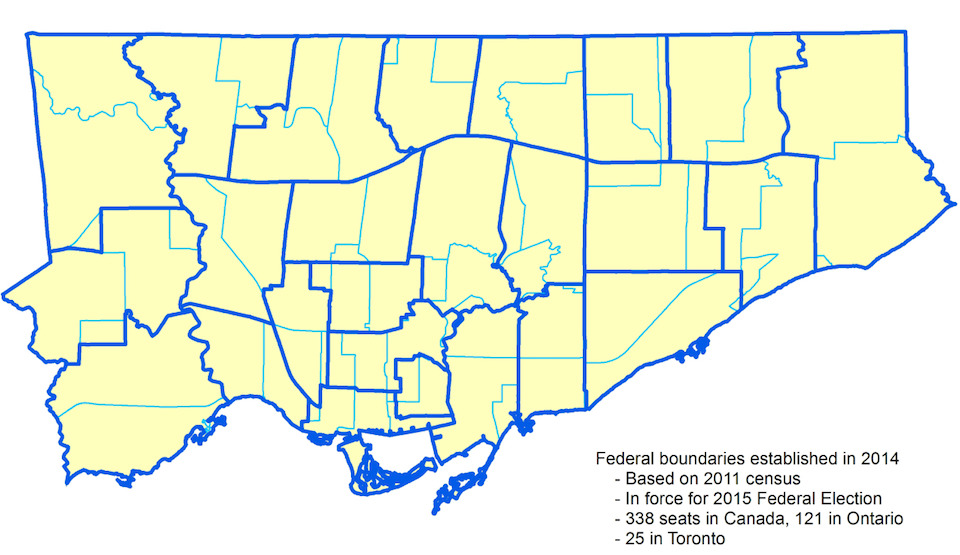

Toronto 2015 federal riding boundaries overlaid on 2014 municipal ward boundaries, image courtesy of Sean Marshall

Toronto 2015 federal riding boundaries overlaid on 2014 municipal ward boundaries, image courtesy of Sean Marshall

Discussion of councillor-to-constituent ratios among the chattering classes and tabloids, alike, has, predictably, led to the propagation of some very bad math and worse comparisons. Ford himself, never shy to employ misleading or plainly inaccurate data to make a point, offered up Los Angeles as an example of a city whose governance is a model of lean efficiency that Toronto should follow, despite the fact that the two cities have drastically different governance structures. Some have also held up London, UK as a comparison, a similarly bad one given that under its 25-person Assembly (their Council) sit more than 30 separate borough councils, some even with their own mayor.

For an example closer to home, we can look to Ottawa, which has 23 councillors serving a population of less than one million people, meaning each councillor represents roughly 40,000 people. Ottawa is, of course, also a city in the province of which Doug Ford is premier, but will curiously not have its council slashed. After the October election, each Toronto councillor will represent 60,000 more people than their Ottawa counterparts. As democracy activist Dave Meslin said last week on Twitter, Toronto now finds itself in a “crisis of under-representation.”

But getting bogged down in the ins and outs of the arguments for and against the different models of representation distracts from the central reality of the fight, which is that the debate is, at its core, a political one. One of the consequences of the 47-ward structure was to be the creation of new downtown wards (where most of the city’s growth has occurred), which would have shifted the balance of power away from the suburban councillors who tend to vote to the political right of most downtown councillors, and who form the core of Mayor Tory’s support on Council.

Toronto 2018-2022 wards as approved by the OMB, image by City of Toronto

Toronto 2018-2022 wards as approved by the OMB, image by City of Toronto

This mid-election upheaval — and the associated political consequences it will bring about — comes at a critical time in which Toronto is grappling with substantial and complicated issues that require serious action and, in many cases, investment. The next council will have to tackle a rise in gun violence that was sweeping through the city this summer even prior to the massacre on the Danforth, and an historic road safety crisis that is also killing our neighbours. It will have to confront a Toronto Community Housing waitlist that has as many people on it as live in Peterborough, and an affordability crisis that affects hundreds of thousands more. It will need to make smart, demand-based transit investments to ease the city’s crippling gridlock.

All of these areas are ones in which Toronto’s suburban councillors and Mayor Tory have been hesitant to invest, despite maintaining steadfastness in their support for a one-stop suburban subway extension with a current price tag of $3.35 billion, and an updated costing to come early in the next council term.

Ford, who famously often decries “latte-sipping downtown elites”, was rejected by nearly 70% of Toronto voters in the last mayoral election. His PC party swept to power with a commanding majority in the recent provincial election, despite failing to win a single seat in downtown Toronto.

Ford holds a dangerous grudge against the people who have consistently rejected him. Partisan gerrymandering is fairly tough to accomplish in Canada, but Ford has managed that feat, and is soon to have his revenge. Previously known by most as “Rob Ford’s brother” until a strange sequence of events catapulted him into the premiership, perhaps “Dictator Doug” is a more fitting moniker for the rookie premier.

* * *

Alex Mather is a Toronto-based political strategist who has advised political parties, non-profits, and advocacy organizations across North America and Europe. You can follow him on Twitter @AlexDRMather.

2.2K

2.2K