By any account it is a remarkable survivor. The city around it has served as a lab of sorts, an ephemeral testing ground for the social engineering of well-intentioned urban planners. The revisions to Regent Park have penetrated so deeply that even something as foundational as the city's network of streets have been erased only to later reappear. Within this context, the survival of any historic building is noteworthy. To have that same structure thoughtfully augmented and restored is a cause for celebration. The LEED silver retrofit of Nelson Mandela Park Public School by CS&P Architects is home to 660 students in a K-8 setting in addition to a City of Toronto child care centre, community centre and employment centre linked to the Toronto Community and Housing Corporation.

Shuter Street frontage of Nelson Mandela Park Public School (pre-renovation), image by Forum member spmarshall.

Shuter Street frontage of Nelson Mandela Park Public School (pre-renovation), image by Forum member spmarshall.

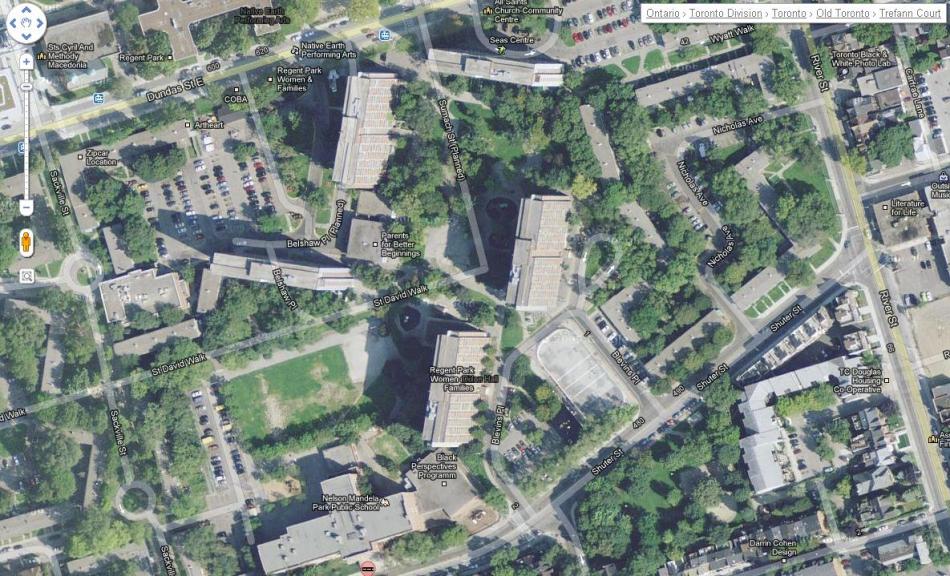

Aerial perspective of the site with the school visible in the lower left. Regent Park South can be seen in the centre of the photo. Image sourced from Google Earth.

Aerial perspective of the site with the school visible in the lower left. Regent Park South can be seen in the centre of the photo. Image sourced from Google Earth.

The renovation of the school incorporates design elements that are reflective of recent pedagogical changes including a focus on collaboration, openness and the fostering of a dynamic learning environment. As explained by lead architect Maureen O'Shaughnessy, the retrofit of the school sought to create an environment in which "casual encounters" between students would be possible and where the stiff formality of the "factory model" of academic design would be loosened. A defining component of this design is a tiered amphitheatre in the centre of the school that links the lower and ground floors together. The central location of the airy space allows for the spontaneous and relaxed interaction desired by both the school board and the project’s design team. Coupled with the push for greater openness is a need to soften the monumentality of the space within the building, leading to the creation of "nooks" where more human-scaled spaces can be found.

Rendering of the tiered amphitheatre in the centre of the school, image courtesy of CS&P Architects.

Rendering of the tiered amphitheatre in the centre of the school, image courtesy of CS&P Architects.

Completed amphitheatre, image courtesy of CS&P Architects.

Completed amphitheatre, image courtesy of CS&P Architects.

One of the school's new labs, image courtesy of CS&P Architects.

One of the school's new labs, image courtesy of CS&P Architects.

View of the renovated interior, image courtesy of CS&P Architects.

View of the renovated interior, image courtesy of CS&P Architects.

This emphasis on creating a light-filled transparent space is one that is duplicated throughout the school, one that "respects the framework of the school [while] allowing for more openness and less rigidity." The new library also showcases these principles through the enlargement and consolidation of the space into one room. Opting for entrances without doors allows for an easier flow of people and the creation of a welcoming meeting space. The effect is a wonderful nurturing of social interaction that feeds into the vitality of the new school. Classrooms too have been brightened with the replacement of their narrow opaque doors with large glazed glass screens that allow more light to enter.

A view of the school's new, expanded library. Image courtesy of CS&P Architects.

A view of the school's new, expanded library. Image courtesy of CS&P Architects.

Play area and new addition to the school housing the Child Care Centre and north Kindergarten, image courtesy of CS&P Architects.

Play area and new addition to the school housing the Child Care Centre and north Kindergarten, image courtesy of CS&P Architects.

Outdoor space complete with artificial turf field, image courtesy of CS&P Architects.

Outdoor space complete with artificial turf field, image courtesy of CS&P Architects.

The inclusion of multiple community supports into the project is a central tenet of the redesign and serves as a template for the Toronto District School Board's Model Schools for Inner Cities Policy. By combining an employment centre, child care facilities and a community centre into a single hub, the complex provides a level of support for and connection to the community that would otherwise not be possible with a school alone. The strength provided by this synergistic approach to neighbourhood building is viewed as a means to aid marginalized communities where the pervasive and harmful effects of poverty extend beyond simple material deprivation to include limitations on social mobility. Significant too is the responsive and inclusive approach to the redevelopment project. Consultations with local stakeholders, the school board and the design team ensured that the end product was one that was crafted to meet the needs of all the parties. This receptiveness will ensure that the project will feed into the positive energy of the revitalized Regent Park and become an "essential and identifying" piece of the community.

Coupled with the progressive social aims of the project is an admirable respect for our built heritage. Despite an increasing awareness of the importance of architectural preservation, there remains a relatively shallow commitment to the cause if the costs of retention are anything but marginal. The team led by O'Shaughnessy has successfully built upon the "strong bones" of the Beaux-Arts structure, namely the high ceilings, huge rooms and Terrazzo floors to create a space that suits the contemporary needs of the school while retaining the defining features of the heritage property. Given the TDSB's considerable holdings of heritage properties, including a sizable collection of modernist buildings, this project is a positive template for future school rehabilitations; demonstrating that it is possible to celebrate heritage while ensuring practicality and efficiency in its adaptation and reuse.

The project, however, is not without controversy. A significant cost overrun has marred the otherwise successful renovation. Initially reported to be as high as $11 million, the TDSB reports that the true figure is closer to $4 million. Out of a total budget of $21.7 million this constitutes a sizable 18% deviation from the anticipated total and is representative of an ongoing struggle for the cash-strapped board to bring projects to completion on budget. This endemic problem led to a provincial funding freeze for the TDSB's capital budget as 25% of the projects undertaken by the board have run over budget. It should be noted that much of the reporting on this issue has failed to take into account the obstacles faced by the board that were largely out of their control, some of which are the unfortunate but necessary consequences involved in heritage restoration. Difficulties with land transfers between the TDSB and both the City of Toronto and the TCHC added to the cost of the project as did challenges accessing the site amidst the substantial construction work underway in Regent Park. Contaminated soil unearthed in the basement of the school along with severe corrosion of the building's cast-iron structural supports posed additional problems during the renovation. The latter two of these issues are the type of expensive obstacles inherent to preservation work and should receive a more sympathetic treatment than cost overruns brought about by improper planning or bureaucratic errors.

It also raises an important question as to how much we as a city value our built heritage and whether subjecting these projects to a cold market calculus will be successful in determining their true value. Our architectural history is, afterall, a non-renewable resource whose destruction leaves a cultural deficit that is often greater than the cost of its retention.

Urban Toronto would like to thank Maureen O'Shaughnessy for her time and input. To learn more about CS&P's work, a link to their portfolio of work can be found here.

2.9K

2.9K